Susana Puig, dermatologist: "A tan is the body's response to skin damage; there's little point in seeking it out."

Dermatologist Susana Puig (Barcelona, 60) is grieving. For good reasons, in this case, but a grieving process nonetheless. This doctor, head of Dermatology at Hospital Clínic, has just been appointed director of the August Pi i Sunyer Biomedical Research Institute (IDIBAPS), the scientific institution affiliated with the Barcelona hospital. She's happy and eager to take on the challenge, but the new position will take up most of her time from now on, and, in addition to giving up command of the medical service, she will have to reduce her direct care of her patients. And that's going to be difficult, she admits. "For me, the doctor-patient relationship is fundamental. I manage families with familial melanoma, including the first patient during my doctoral thesis in the 1990s. One of the positive aspects of this profession is the relationship with people and being able to help them, the bond with patients," she explains.

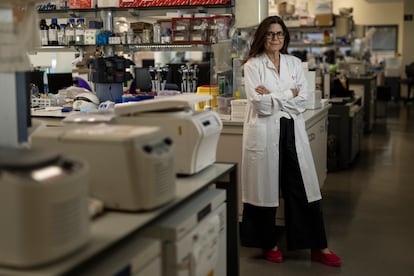

Puig is the first woman to lead Idibaps, a cutting-edge biomedical research center with 30 years of history. The scientist, who also leads the Melanoma: Imaging, Genetics, and Immunology group at this institution and is a professor at the University of Barcelona, speaks to EL PAÍS in her office, still empty and still in the process of moving. Her new chair is a stone's throw from the hospital, a location that perfectly matches her obsession with advancing the development of translational research: science leaves the clinic and must return to the clinic, she insists.

Question: The rise of the far right, Trump's cuts to research centers, the leadership of the US National Institutes of Health in the hands of a person who spreads anti-vaccine messages... Is science more challenged than ever?

Answer: It's questionable, but at the same time, these people are the ones who consistently use pseudoscientific vocabulary. They're against it, but they use it for their own benefit. We're in a complicated time , where science has reached levels we couldn't even imagine in a very short period of time. And this profound knowledge in all aspects, including human behavior, I think can frighten some leaders, and that's why they're trying, in some ways, to prevent this progress in knowledge.

Q. Do you fear that there will be a halt in the advancement of scientific knowledge?

A. This is very unlikely to stop. We're now generating more knowledge much faster. Artificial intelligence tools allow us to analyze data at stratospheric speed , and all these new technologies being designed allow us to question things that were previously unthinkable. Therefore, I hardly see a massive destruction of science. Yes, there could be a slowdown, and of course, science needs investment. And one of the big problems is that in many institutions, we're advocating for open science and sharing. And there's a danger that science will be swallowed up by a darker industry whose goal is to have closed science for the benefit of a few lobbies. This is where this battle will take place.

Q. Is Trump's science cuts policy taking its toll on Idibaps?

A. We have collaborators with the United States, of course. And above all, there is great concern. And even some articles or projects have been somewhat delayed. But we need to fully analyze what this could entail . I don't want to be alarmist, but we should be alert because we live in a global world, and decisions made in the United States at the scientific level can have repercussions. But they can also have other positive aspects, such as seeking collaborations elsewhere or making researchers more inclined to return or not leave. It's an opportunity we should understand, but we will have to create the positions, spaces, and funding to make this happen.

Q. What might be the long-term implications of all this shake-up in science?

A. In humans, we always have a bit of a pendulum swing: there comes a time when science seems to have to solve everything, and then we can return to a somewhat obscure period, where we stop believing in objective, scientific data and start to have obscurantist beliefs. It's possible that it could happen. My impression is that now, in such a global world where all information is so accessible, it's possible for both currents to coexist in different areas of the planet.

Q. How do you combat pseudoscience?

A. One would like to think that scientific data should be able to counteract all this pseudoscience, but in reality, it's emotional attitudes, like fandom for a football team. Perhaps we should try to understand what's behind it. Often, it's fear, and perhaps if we could understand why this fear exists, what its origins are, we could change this whole perception.

Q. Your area of research is melanoma. Just 15 years ago, a revolutionary immunotherapy was introduced for this skin cancer. How has that changed?

A. A lot. At that time, the average life expectancy for a metastatic melanoma patient was six months, and now it's five years. It's a very significant change. Although, of course, when we say this, 50% of patients are no longer here after five years. So, there's still a long way to go.

Q. How do melanomas interact with lifestyle habits? Is sun exposure the key factor?

A. Exposure to ultraviolet radiation in susceptible individuals—which would be the majority of our population, especially if we suffered burns in childhood or after accumulated radiation—may be implicated. But other factors also play an interesting role, including, for example, dietary factors. It's worth noting that coffee has been shown to be protective against melanoma and also non-melanoma skin cancer. Other interesting factors include stress, which in some ways causes immunosuppression, and sleep disorders, which we've also seen may be implicated in the development of melanoma or in the rapid progression of this cancer.

Q. It's summertime now, with crowded beaches. Does the real danger to your skin begin now, or is the risk year-round?

A. The seasons are important. In May, we already have UV radiation levels similar to those in August. The UV radiation we receive today is extremely high, and the days are extremely long: the longest days of the year are in June, and that's, therefore, when we can accumulate the most UV radiation. But now, work is also being done on how UV radiation plus heat further damages our skin and DNA. There's a whole stream of research analyzing how UV radiation affects temperatures and what cumulative, additive, or even synergistic damage looks like when we combine UV radiation with high temperatures.

I say this because it's not the same thing if we go for a walk for five or 10 minutes, come back, cool off... or spend some time exposed to ultraviolet radiation at high temperatures. When people are doing something I'd rather not see, which is tanning, their skin receives ultraviolet radiation at very high temperatures. And current scientific evidence shows that this is much more harmful.

P. Dermatologist Yolanda Gilaberte said in an interview with EL PAÍS that looking for a tan is like looking for a fever.

A. Tanning is the body's response to skin damage. Without damage, you don't get a tan. The body is wise, and when damage occurs to our DNA, our cells, the keratinocytes, produce a hormone that interacts with the surrounding melanocytes and induces a whole series of intracellular responses to produce more melanin. This melanin is then transmitted back to the keratinocytes to try to protect the skin from further damage. So, without damage, there is no tan. That's why there shouldn't be much point in seeking it.

Q. Is there more social awareness about the risks of the sun? Sunscreen is widely accepted.

A. Yes, there's much more awareness, especially among children. It's hard to see a sunburned child these days. And our society has accepted sunscreen much more than clothing and hats. We should change schedules, also emphasize having awnings at schools during the summer months, and limit swimming time during summer camps from 1:00 to 2:00 p.m., which I understand is when it's hot, but it's also when there's a lot of ultraviolet radiation.

Q. There are thousands of skincare products and routines. What does it really take to protect and care for your skin?

A. The trend is toward using a lot of products, and some may be unnecessary or even harmful at certain ages. Young skin needs little more than hygiene. Young skin, when exposed to the sun, needs photoprotection. But one of the things we're seeing is that, thanks to influencers, we have teenagers with routines of eight or nine products that, aside from being a tremendous cost to the family, are producing significant adverse effects, such as comedogenic acne, contact dermatitis... I would sound a bit of a red flag.

EL PAÍS