A scientific team announces the discovery of a new species linked to the origin of humankind.

Fossil hunter Omar Abdulla used to carry an AK-57 assault rifle while roaming his treacherous homeland, Ethiopia’s Afar desert region, disputed by rival tribes. On Valentine’s Day 2018, while descending a hill, Abdulla exclaimed, “Oh my God!” American paleoanthropologist Kaye Reed recalls running toward him and finding him picking up a fossilized tooth in soil about 2.63 million years old. They kept walking and found more teeth. Abdulla was killed in a gun battle in 2021, but Reed and his colleagues continued investigating the teeth and now announce that the remains belonged to a previously unknown species of Australopithecus that coexisted in present-day Ethiopia with early humans. The discovery, published Wednesday in the journal Nature , sheds light on a particularly dark period in human evolution. Three million years ago, there was only one genus in East Africa, Australopithecus . By 2.5 million years ago, there were already three: Australopithecus , Paranthropus , and Homo , the scientific label for humans.

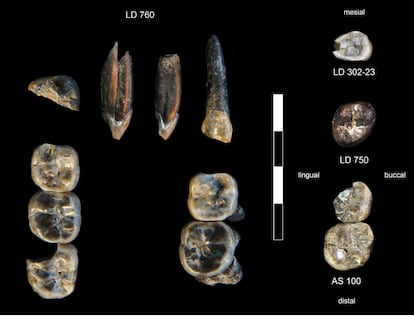

“It was an exciting day,” Reed recalls. Her team ended up finding a dozen strange teeth, large and with small morphological changes. They didn’t match anything known. The last known Australopithecus afarensis —like Lucy, the famous female whose remains showed that these human ancestors already walked upright—lived about three million years ago. Perhaps they were the first Australopithecus garhi , another species that lived in present-day Ethiopia 2.5 million years ago, but the teeth were different. For Reed and her colleagues, there is only one hypothesis that fits the data: a new species of Australopithecus, still unnamed. “We need to find something with more characteristics, like a skull or a skeleton. I wish we had that already,” explains the researcher, from Arizona State University.

Two decades ago, Reed worked at the Paleolithic site of the Sopeña cave in Asturias . She fell so in love with the place that she decided to spend a sabbatical there between 2005 and 2006, living in the village of Benia de Onís and walking every afternoon along its shepherd's paths. Three years earlier, Reed had begun a research project in Ledi-Geraru, in Ethiopia's Afar region. In March 2015, her team announced that they had found a fragment of a jawbone with teeth there, attributed to an individual of the genus Homo that lived about 2.8 million years ago. It was, they proclaimed in the journal Science , the earliest known human .

In addition to the 10 Australopithecus teeth, the American scientist and her colleagues have found three other teeth that they believe belong to an unidentified human species, between 2.59 and 2.78 million years old. The team argues that their discoveries demonstrate that these lineages lived in the Afar region at the same time. Did they coexist? Did they fight? It's unknown. Reed emphasizes that the classic view of human evolution, as an arrow that runs from ape to Homo sapiens via Neanderthals, is completely wrong. The paleoanthropologist speaks of a "leafy tree," in which branches intersect and tangle, with species that go nowhere and simply become extinct.

American Tim White , a living legend of prehistory, believes the new findings are unconvincing. When he was still in his twenties, in 1979, White was one of the scientists who announced to the world the discovery of Lucy, the one-meter-tall, small-brained Australopithecus afarensis that walked upright some three million years ago in what is now Ethiopia. The researcher emphasizes that the Ledi-Geraru area is only a few dozen kilometers from Hadar, where Lucy's partial skeleton was found. Erosion, White explains, has meant that Hadar lacks sediments around 2.7 million years old, as there are in Ledi-Geraru.

The paleoanthropologist argues that the new teeth fit into the lineage that evolved over half a million years from Lucy and the rest of Australopithecus afarensis to their “direct descendants,” Australopithecus garhi , a species that White himself and five other colleagues described in 1999 as a possible ancestor of early humans. “The authors wrongly maintain that the last appearance of Australopithecus afarensis was 2.95 million years ago. Consequently, they make the extraordinary claim of having found a new species, rather than the hoped-for evidence of the evolution of Australopithecus afarensis ,” says White, who moved to Burgos in 2022 to join the National Center for Research on Human Evolution (CENIEH).

“The authors’ claim that it’s a new species of Australopithecus is even less convincing than their parallel 2015 claim in Science that a jaw fragment from their study area represents the earliest Homo , at 2.8 million years old. I expect both claims to be refuted when new fossils are discovered,” adds White, who is highly critical of the peer-review processes of these scientific journals. “It’s more reasonable to interpret both the jaw and teeth as having belonged to more recent, slightly evolved members of Australopithecus afarensis , Lucy’s species. However, it seems that such a conclusion would not satisfy Nature ’s apparent need for paleopublicity ,” he concludes.

Researchers Marina Martínez de Pinillos and Leslea Hlusko , also from CENIEH, are studying fossil teeth from Omo, in southern Ethiopia, trying to distinguish whether they are from Australopithecus or Homo . Their preliminary results suggest that isolated teeth from that dark period cannot be identified with that degree of specificity and certainty. “During this 500,000-year interval, an evolutionary line from Australopithecus gave rise to Homo and/or Paranthropus . Hundreds of hominin fossils are known from this period, the vast majority from the same geographic region, and they include numerous teeth. These previously described fossils reveal a large overlap in dental variation during evolutionary transitions. The 13 new teeth do not show any unique traits that differentiate them from the already known fossils of Australopithecus afarensis and the earliest representatives of the genus Homo ,” the pair note in a joint response to this newspaper's query.

Martínez de Pinillos and Hlusko emphasize that, when working with isolated teeth, it's easy to misinterpret the differences. No two molars are alike, but the line between normal variation within a species, gradual evolutionary change, and the existence of a new species is very blurred. "From our perspective, the extraordinary claim that some of these teeth represent a new species of Australopithecus requires extraordinary evidence, and, unfortunately, this set of teeth doesn't provide it," they conclude.

The director of the CENIEH, María Martinón , is also skeptical. “Although the sample is relevant and describes in detail the morphological variability existing in the region, I believe it may be premature to conclude that it is a new species of Australopithecus. The differences with Australopithecus afarensis do not seem robust enough to me, and the traits analyzed show a wide overlap that could be due to local or temporal variation,” she says. “I agree that the evolution of our ancestors was not linear and that we should be open to more complex patterns, with the possible coexistence even of different genera. This could be explained by adaptations to different ecological niches—such as variations in diet—which would have reduced direct competition between them,” she adds.

Manuel Domínguez Rodrigo , co-director of the Institute of Evolution in Africa associated with the University of Alcalá, has worked on exceptional African sites, such as those at Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania. This expert believes that the Ledi-Geraru teeth may have belonged to Australopithecus afarensis, more recent and evolved than Lucy, or to a new, "highly similar" species. In his opinion, this discovery documents that there were at least four evolutionary lineages "coexisting" in East Africa at the time the human race emerged: Australopithecus , Paranthropus , the controversial Kenyanthropus from Kenya, and the nascent Homo itself, characterized by an enlarged brain, reduced tooth size, the use of stone tools, and meat consumption, according to the researcher.

“This indicates that it was a period of major environmental change that led to a reshaping of all the faunas that existed in East Africa, including the hominins [hominids with bipedal locomotion and upright posture]. Each of these branches is an evolutionary experiment. After two million years, only two survived: Homo and Paranthropus ,” says Domínguez Rodrigo. The Paranthropus were similar to more robust Australopithecines, but they became extinct just over a million years ago. Whatever the evolution and competition between the multitude of species that coexisted, only one remained: modern humans, whose only predator is Homo sapiens itself, as demonstrated by the murder of Omar Abdulla, the man who found the first teeth in Ledi-Geraru on that Valentine's Day.

EL PAÍS