The goal of science is not to speak to everyone, but to speak honestly to those who want to listen.

Handle

Bad scientists

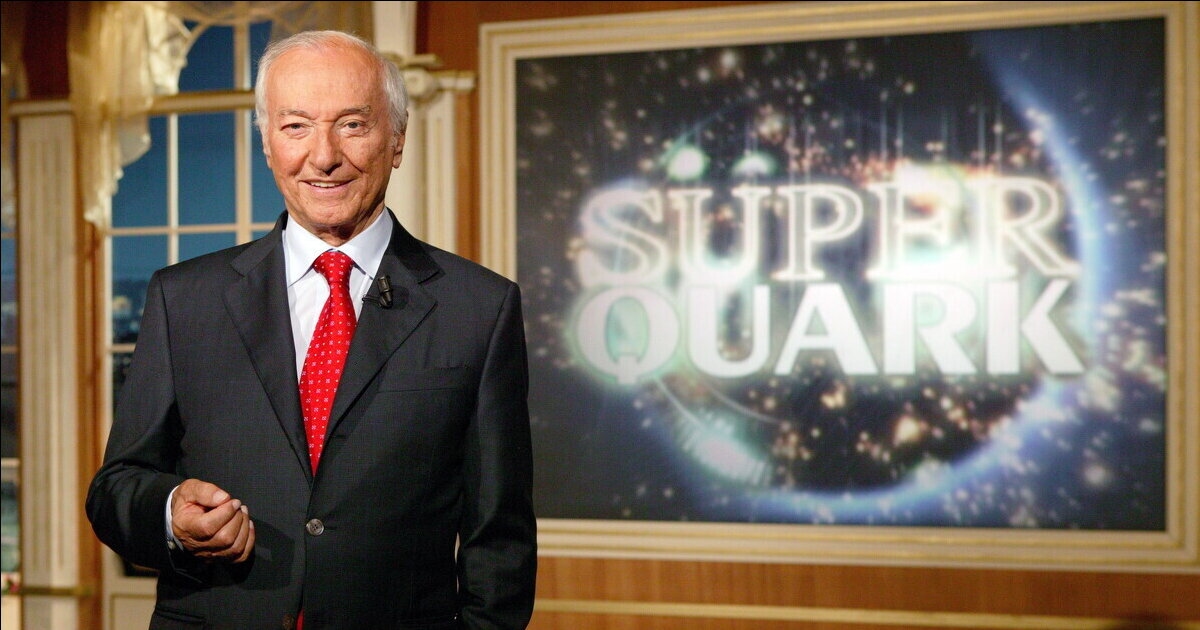

Attempting to engage in dialogue with those who reject the scientific method on principle is futile because their rejection affects the very idea of verification. But that doesn't mean we should stop disseminating information. As Piero Angela was one of the first to demonstrate, there exists a segment of citizens who are curious and attentive.

On the same topic:

"Discuss it among yourselves scientists," "there's no point splitting hairs," "the majority of readers will never understand these things anyway." These are phrases we often hear whenever a researcher or science communicator attempts to explain the more delicate aspects of a scientific result in public: for example, as I did yesterday , the extent of uncertainty, the degree of data reliability, the logic behind a conclusion. At first glance, they seem like common-sense observations. Not everyone has a technical background, and discussing numbers, margins, or probabilities can seem like a specialist's exercise. In reality, this belief—that the public should be protected from complexity—I believe is the main cause of the gap between science and society. Let me preface this by saying: I don't have the professional training that good science communicators have, and I speak only from my limited direct experience, resulting from my efforts to communicate to the public, and often also to better understand with the public, some scientific fact that I find relevant. However, I believe that, having often received comments like those at the beginning of this short article, it may be worth explaining my position on the matter, by way of a response.

I believe that trust in scientific information doesn't arise from simplified messages, but from the ability to follow a step-by-step reasoning and its accuracy. When communication reduces everything to short formulas—"the vaccine works" or "it doesn't work," "it's safe" or "it's not safe"—it produces fragile information, ready to collapse at the first update of the data. Of course, this communication fulfills a very useful social function, especially in an emergency, which is to provide expert guidance to those who have chosen to trust the experts; however, that's not what I aim for when I communicate scientific results. Explaining the conditions and limitations of that result, however, allows us to understand its solidity and accept that it can be revised without diminishing its credibility. Scientific knowledge is a dynamic system: it improves by measuring its own limits, and this very capacity for self-verification makes it reliable. I don't believe science communication can be done without constantly taking this into account and reflecting these concepts in the words. Furthermore, I believe that good dissemination does not primarily serve to persuade, but to make visible how science constructs and controls its results, and how and why certain ideas are wrong.

"Sure, but go explain these things to anti-vaxxers," my objector would say. Not to them, I reply. We all know that attempting to engage in dialogue with those who reject the scientific method on principle is futile, because their rejection isn't about content, but the very idea of verification. An anti-vaxxer or a conspiracy theorist is defending an identity, not an argument: for them, rational discussion is merely an opportunity to reaffirm their affiliation. In these cases, at most, it's a matter of preventing public discourse from losing its criteria of coherence. Disclosure to an anti-vaxxer is therefore simply pointless, but the fact that it's pointless for them doesn't mean we should stop disseminating information.

Moreover, even in the absence of interlocutors willing to understand, it is sometimes necessary to respond. Doing so serves not so much to change the minds of those spreading falsehoods as to protect those who observe. When phrases like "vaccines modify DNA" or "pharmaceutical companies hide side effects" circulate, a public clarification provides context, sources, and verification. The same is true for videos that manipulate graphs or contagion curves to invent nonexistent correlations: explaining where and how the distortion occurs helps reestablish the rules of rational discussion. From this perspective, even the "Burioni method"—short, ironic, sometimes cutting, insulting, and irritating responses, but always grounded in verifiable data—had and has a specific function: not to convert deniers or to explain, but to point out that there is a limit beyond which discussion ceases to be reasonable, without, in fact, wasting dissemination on those who might never be truly interested. This, I believe, is where the central issue arises: those who communicate science must know who they are addressing. There is no single, undifferentiated audience.

As Piero Angela was one of the first to demonstrate, there exists a segment of citizens who are curious, attentive, willing to concentrate and make a small effort to understand. It is to them that dissemination must be addressed. They are people who want to learn the results obtained, understand the processes, see how knowledge is constructed and refined, and understand why a result is only as valuable as the transparency of the method that produced it. These people do not necessarily already have a clear idea about a topic; indeed, they are often interested in evaluating the various arguments, to then decide which is most convincing. It is to them that it is worth dedicating time, rigor, and clarity, demonstrating the strength of the method: only in this exchange can knowledge circulate authentically.

Then there is a segment of opponents of scientific discourse and science itself, who in this historical period even manage to bring people like Robert Kennedy Jr. to power, systematically filling newspapers with lies, and attacking and insulting in order to defend outrageous lies, which, however, serve to strengthen their own tribe (and benefit those who invent them to extort money). With these people, there is no dissemination or discussion of data ; as long as there is the patience and strength, they should be denounced, unmasked, and reported to the public (or to law enforcement, if applicable), without even worrying too much about the resulting polarization, because, in fact, their ideas are already polarizing, and because it has been demonstrated all too often what happens when they are left free to roam.

Ultimately, I believe the goal is not to "speak to everyone," but to speak honestly to those willing to listen. Communication designed to appeal to everyone ends up resembling advertising or a show: immediate, emotional, reassuring, and lacking substance. Science requires a different pace: attention, patience, and cognitive engagement on both sides. Those communicating must avoid jargon without sacrificing rigor, and above all, must demonstrate utmost honesty in their reasoning and in the presentation of facts and data; those listening must accept that understanding requires time, precision, and some difficulty. Roles are not rigid: sometimes our interlocutor knows more, or discovers a flaw in the very reasoning we were using, but since we share a common method, it's easier to resolve conflicts of interpretation. From this balance, trust is born.

More on these topics:

ilmanifesto