There is faith in desire

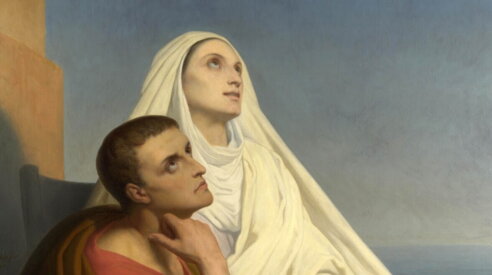

detail of the painting by Ary Scheffer, “Saint Augustine and Saint Monica”, oil on canvas, 1854

magazine

So our search for happiness is a mirror of God's existence. Theology, the only possible one, speaks of Him.

The Church is the only company in the world where there is no complaints office. In fact, it would make no sense, since customers who are dissatisfied with the afterlife product offered to them by the Church, namely heaven, eternal happiness, can no longer complain: they are dead. And yet everyone, absolutely everyone, is interested in it. Is there a better business than this? There is a market share as big as the entire pie, namely a demand that concerns all men, the demand for happiness. The Church offers precisely this, eternal happiness, to everyone, at the ultimately acceptable price of some sacrifice (Pascal's wager docet), delivery takes place in the afterlife, no one can complain. Brilliant.

It is clear that a business of this type could not fail to attract the interest of another multinational company, that of employers around the world, of bosses as they used to say. Why? Simple, because the promise of a happy afterlife is very useful to better endure poverty, unjust and inhuman working conditions, in short to keep workers, the poor, the homeless and the hopeless calm and happy.

It is no wonder, then, that the Church and the aristocracy in the past, and then in modern times, the Church and the bourgeoisie have gone hand in hand for centuries, and now passionately embrace each other in North America.

In South America, on the other hand, liberation theology was born. Liberation from what? From misery . It is the Marxist theology that also influenced Pope Francis. Christ did not come to earth, the South American theologians said, only to announce happiness in heaven, but to console the afflicted already in this world . It is the Gospel that says so: "Go and tell John what you hear and see: the blind receive their sight, the lame walk, the lepers are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised, the good news is preached to the poor" (Mt. 11,4-5). In short, if it wants to remain faithful to the Gospel, the Church cannot help but be on the side of those who here and now are sick, poor, migrants, the last . Liberation theology says that the Church's business is not the afterlife but everywhere here on this earth there is suffering and misery.

It is understandable why during the pontificate of Pope Francis the left all over the world, short of political ideas, rejoiced and the right instead denounced the syndicalist and communist drift – two offensive words among the rich conservatives of the whole world – of a Church that had been on their side for centuries. And now? Which side will Pope Leo XIV be on? Of course it is still very early to understand but I really liked his first homily, in the Sistine Chapel, when he recalled "the indispensable commitment for anyone in the Church who exercises a ministry of authority: to disappear so that Christ remains, to make oneself small so that He may be known and glorified (cf. John 3:30)."

It reminded me of a Mass I attended years ago in Lugano. It was August, and the church was mostly populated by tourists who didn't know Father Domenico. The media were reporting serious news stories from around the world and everyone was expecting a moralistic comment in the homily: oh no, that's not how it's done. Instead, Father Domenico spoke of nothing but God. He disappeared. It was like a finger pointing toward Heaven, a window onto the Invisible. At the end of the homily there was a brief moment of silence, then spontaneous applause broke out. For whom? To me it didn't seem like applause for Father Domenico but, I think, for God himself, if that were truly possible. We were grateful and happy to have listened to a Vicar of Christ who didn't let the news dictate his agenda, but who, with extreme simplicity, spoke to us about God, how he was and how he wasn't: eternal, infinite, immutable, good, perfect and so on. Beautiful. It was the homily of a true theologian, because “theology” means nothing other than this: discourse (logos) on God (theos).

I have been a member of the commissions for the competitive examinations for the chairs of dogmatic theology and fundamental theology in Switzerland. I was surprised to see that many theologians now only deal with things like ecotheology, zootheology, neurotheology, anarchotheology, gender theology, transhumanist theology, digital theology, and even food theology or gastrotheology. (German) theologians write about everything except God.

Better Father Domenico, at least he spoke to us about the names of God and, just by simply speaking about them, he filled our hearts.

I have studied Thomas Aquinas' treatise on God in the Summa Theologiae for years, and recently, thanks also to discussions with my philosophy students in Zurich, and to rereading the medieval Jewish theologian Moses Maimonides, I have understood perhaps why talking about God is so comforting.

Let us take the treatise on the attributes or names of God: according to Thomas Aquinas, He is simple, perfect, good, infinite, immutable, eternal, one, omniscient, true, alive, loving, just, merciful, omnipotent, happy, generating, relating, personal. What is the common thread that ties all these attributes together? It seems to me to be a desirous thought or, simply, desire.

In life we painfully experience the consequences of our own and other people's imperfection, for example in the failure of a love story: how beautiful it would be, our longing mind tells us, to meet a perfect being, who does not make mistakes, and therefore does not hurt even unintentionally because of his imperfections and weaknesses, who does not do harm: theology explains that God is precisely that perfect being. History is dripping with blood because of the hatred that brutalizes men and peoples, so we cannot help but desire the opposite of what we experience: God, we are told, is good and loving. We do not trust turncoats: God is immutable. We are saddened that beautiful things must end sooner or later and loved ones must die: God does not end, He is eternal. We feel dull and apathetic: God is alive. We are unhappy: God is happy. We feel alone: God, one and triune, is never alone (Ratzinger's homily at the funeral of Pope John Paul II is famous in this regard). The discourse on God, therefore, theo-logy, also seems like a sort of map of the human desire for happiness in all its facets, a poignant symphony of desires, a fresco of suffering and hopes, a Dantean Divine Comedy in tercets of reasoning and biblical passages.

I have always been struck by the theological disputes on the nature of God, all heated, vehement. And yet, they deal with a subject that is ultimately unverifiable, on which it would be impossible to have absolute certainties. Each position has biblical citations and good arguments on its side. Let's take for example the most heated theological dispute currently underway in English-speaking countries, with hundreds of publications all over the world (and then they say that "God is dead", where? Perhaps only in some European countries): on one side classical theism, on the other process theology and open theism. The first maintains that God is immutable, the second maintain, instead, that God changes, becomes. The defenders of the first current argue that, if God changed, he would be imperfect; the supporters of the other two currents believe, on the contrary, that precisely if he did not change, he would be imperfect. I like to call the former “mountain theologians”: they imagine that God is a kind of mountain, stable, fixed, immovable. And just as an unstable, crumbling mountain would not be a true mountain, a perfect mountain, so a mobile God would not be perfect. The latter seem to me instead to be “sea theologians”: they imagine God as the sea, immense but mobile, changing, wavy. And just as a still sea would be a dead sea, a pond, a swamp, and would not be a true sea, a perfect sea, so an immobile God would be devoid of vitality, imperfect.

The former say: God cannot not be immobile; the latter say: God cannot not be mobile. Why “cannot not be”? Is it a logical necessity based on irrefutable rational arguments? It doesn’t seem so: both have good arguments on their side, as we have just seen. So what? It seems to me that the vehemence of the dispute has to do with a moral and psychological necessity, based on desire.

Mountain Christians desire, indeed they really need certainties, and the image of the mountain, planted there, immovable, reassures them. Seaside Christians, on the other hand, hate stagnation and dream of movement and change, so the image of the sea with its waves gives them hope. Perhaps the former are inherently insecure and the latter eternally dissatisfied with the present. In any case, the reasoning of desirous thought is understandable: for the insecure, God cannot but be immovable, like a mountain, otherwise their need for security would be frustrated; for the dissatisfied, God cannot but be mobile and changing, otherwise their desire for change and novelty would be in vain. Perhaps it is these needs and these desires that make them say: “there must be an immobile Being” or “there must be a becoming Being”.

In any case, as we can see, theology – precisely that understood in the classical sense as a discourse on God, not as gastrotheology and similar things – has to do with the desires, needs, and deep emotions of man.

This theology is by its nature also eschatology, that is, discourse on the end or final destiny of man, that is, on the afterlife, on paradise. By its nature, in fact, this is in accordance with the deepest human desire. Otherwise, what kind of paradise would it be?

It is therefore clear why speaking of God is truly consoling. In participating in the life of an infinite, immutable, eternal, happy God and so on, in a word, most perfect, that is, exactly the opposite of our imperfect and unhappy human experience, desire finds peace. Only of such a God, as classical theology describes him, can it truly be said that, at the end of time, “he will wipe away every tear from their eyes; there will be no more death, neither will there be mourning nor crying nor pain anymore, for the former things have passed away” (Rev 21:4).

This is why Father Domenico's homilies on God were beautiful: not because they distracted from the problems of everyday news but, on the contrary, because, precisely at the moment in which new news about human misery and violence arrived from the news, they truly intercepted our deep (compensatory) desire.

Yet, without Father Domenico we would not have heard of God, because “no one has ever seen God; the only Son, who is in the bosom of the Father, he has revealed him” (John 1:18). And Father Domenico, in fact, as a true vicar of Christ, revealed God to us, he was a window on earth to Heaven. A window, not a screen, because the screens that surround us shield us and do not open.

Does all this mean that the Church should limit itself to disappearing, to be nothing more than a window, to speak of God and the afterlife without feeding the hungry and giving drink to the thirsty? Certainly not. But it means understanding that no water can truly quench the thirst for happiness, infinite and natural, present in all men, rich or poor. For this reason, all food and water in this world can only be an aperitif of the only banquet that satisfies and quenches thirst, the one prepared by the starred Chef of the Kingdom of God: “Everyone who drinks of this water will be thirsty again; but whoever drinks of the water that I will give him will never be thirsty again” (Jn 4:13-14).

Here Christianity definitively bids farewell to NGOs, which only deal with water that does not quench the desire for happiness. And if the Church does not deal with this desire, who should?

The alternative between a Church for the afterlife and a Church for the present day is false, therefore, because the desire for happiness, that is, for a beyond misery and suffering, is rooted in the depths of the present day.

I can already hear, at this point, the objection of some atheist who, if cultured, might even quote Ludwig Feuerbach: if God is the answer to man's desire for happiness, it means that He is nothing but the projection of this desire and that, therefore, He does not exist. It is known that thirsty men in the desert have mirages, precisely because they are thirsty, but mirages are, precisely, illusions. In English the expression "desirous thought" would be "wishful thinking" which, however, means precisely "illusory thought", "pious illusion", an "opiate" in short, as Karl Marx said.

The objection seems convincing but it is not. Of course, thirst can generate mirages, but if water did not exist and had never existed in the world, could thirst have ever existed? Nature usually does things well: if there is thirst, there is water somewhere. Chronologically, of course, first we are thirsty and then we drink water, but logically, if water did not exist first, thirst would not exist. And in fact, a thirsty humanity without ever having water would have become extinct immediately. Therefore, the existence of thirst can be an indication of the existence of a mirage (an imaginary oasis full of water), but it is certainly also an indication of the existence, somewhere, of water.

How can we be sure of one (mirage) or the other possibility (paradise)? We are not. We can only bet, as Pascal wrote. Of course, we cannot complain, but I believe it is still worth taking the risk.

In the meantime, I would like to ask His Holiness one thing at the beginning of his pontificate: please, speak to us about God. Because only a Church that practices theology in the strict sense, that is, like a window on earth to Heaven, like Christ, reveals God and only Him, instead of discussing many other things of which it is not even an expert, and only a Church that loves eschatology, that is, that speaks of the future, of the afterlife, of heaven, of the Kingdom “which is not of this world” (Jn 18:36), can be faithful to its mission and is more effective than any worldly institution, any NGO, any government. It alone, in fact, takes seriously our irrepressible desire for happiness.

More on these topics:

ilmanifesto