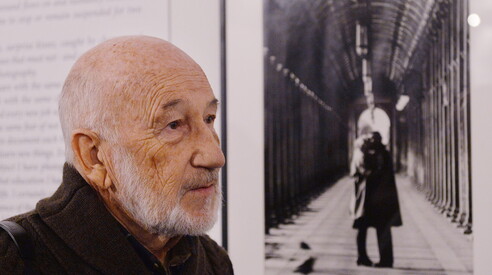

Photography as a profession. Gianni Berengo Gardin has died at 94.

ANSA photo

The anti-myth

He was the dean of Italian photojournalism, but he considered himself a craftsman. While everyone continued to search for him to uncover the secret of his work,

On the same topic:

He repeated until the end that he was not an artist or a poet. "I am a craftsman," he said in the many interviews he gave in recent years: "For me, it's a profession like that of a shoemaker, an engineer, a doctor." Everyone, however, continued to seek him out to discover the secret behind his photographs. And he, not wanting to fall into the trap, repeated that no, it was all thanks to the person in front of the lens. In one of his last conversations with the press, the one given last March to Tempi, Giuseppe Beltrame asked him why people wanted to see him as an artist. And he replied: "Because of the great need to create legends." Gianni Berengo Gardin, the dean of Italian photojournalism, left us today at the age of 94. And he will no longer have the opportunity to oppose the celebration of his legend.

Born in Santa Margherita Ligure in 1930, he grew up in Venice and then settled in Milan in 1965. Like almost all the authors of his generation, he trained as a photographer in amateur photography circles. His was “La Gondola” in Venice, where he met another great name: Paolo Monti. He soon turned professional and began collaborating with Mario Pannunzio's Il Mondo, creating images that would earn him the attention of the most important Italian and foreign newspapers. As a self-conceived craftsman, he dabbled in a bit of everything: from social reportage to architectural and industrial photography. His debut book was “Venise des saisons” in 1965, with texts by Mario Soldati and Giorgio Bassani. In 1969, his images of the Gorizia mental hospital, along with those of Carla Cerati, were selected by Franco Basaglia for the book “Morire di classe,” which the doctor distributed to parliamentarians to encourage the approval of Law 180 . In 1976, with Cesare Zavattini, he also worked in Luzzara, as Paul Strand had done, and the result was "A Country Twenty Years Later," a reinterpretation of the neorealist masterpiece in photography. A myriad of other publications and exhibitions followed in Italy and abroad. The more time passed, the more sought-after he became. Friendly, affable. He was the grandfather of all photographers.

Until the end, he remained faithful to the teachings of Henri-Cartier-Bresson, adopting the paradigm of social reportage, or, if you prefer, humanist black-and-white photography. He created images that reached a wide audience, such as the Beetle on the seashore or the couple kissing under the portico. He was surprised that they were called "iconic," but not overly displeased. He knowingly ignored the sirens of contemporary art, unlike Luigi Ghirri's generation, which paved the way for other shores. With the digital revolution, he vigorously defended analog, starting to stamp his prints with the "real photography" stamp, to certify the absence of Photoshop tricks. By the time artificial intelligence arrived, he was over ninety and had other things to think about . When Beltrame asked him how he felt about death, he replied: "I'm not a believer. I'm not afraid of death, but it makes me angry, because I have to leave behind my loved ones, and the photos, the books, the models I built as a child."

More on these topics:

ilmanifesto