Ricardo Halac, Ñ Lifetime Achievement Award 2025: social, epic, dialectical

You could say it all started with a ball. Ricardo Halac was 13 years old and, like so many kids from Buenos Aires, spent his afternoons in the plaza, amidst shouts, laughter, and muddy cleats. Until a slightly older boy threw out an invitation—like someone casting a line into the Riachuelo River to see if anything bites—"Anyone want to come to the theater?" And Halac , unaware that he was about to change the scene, said yes. That night he sat in the front row. So close to the stage that he could see Discepolín 's hands trembling during the third act, after having seen him suffer a health scare in the second. It was like seeing a god. And that, of course, is something you never forget.

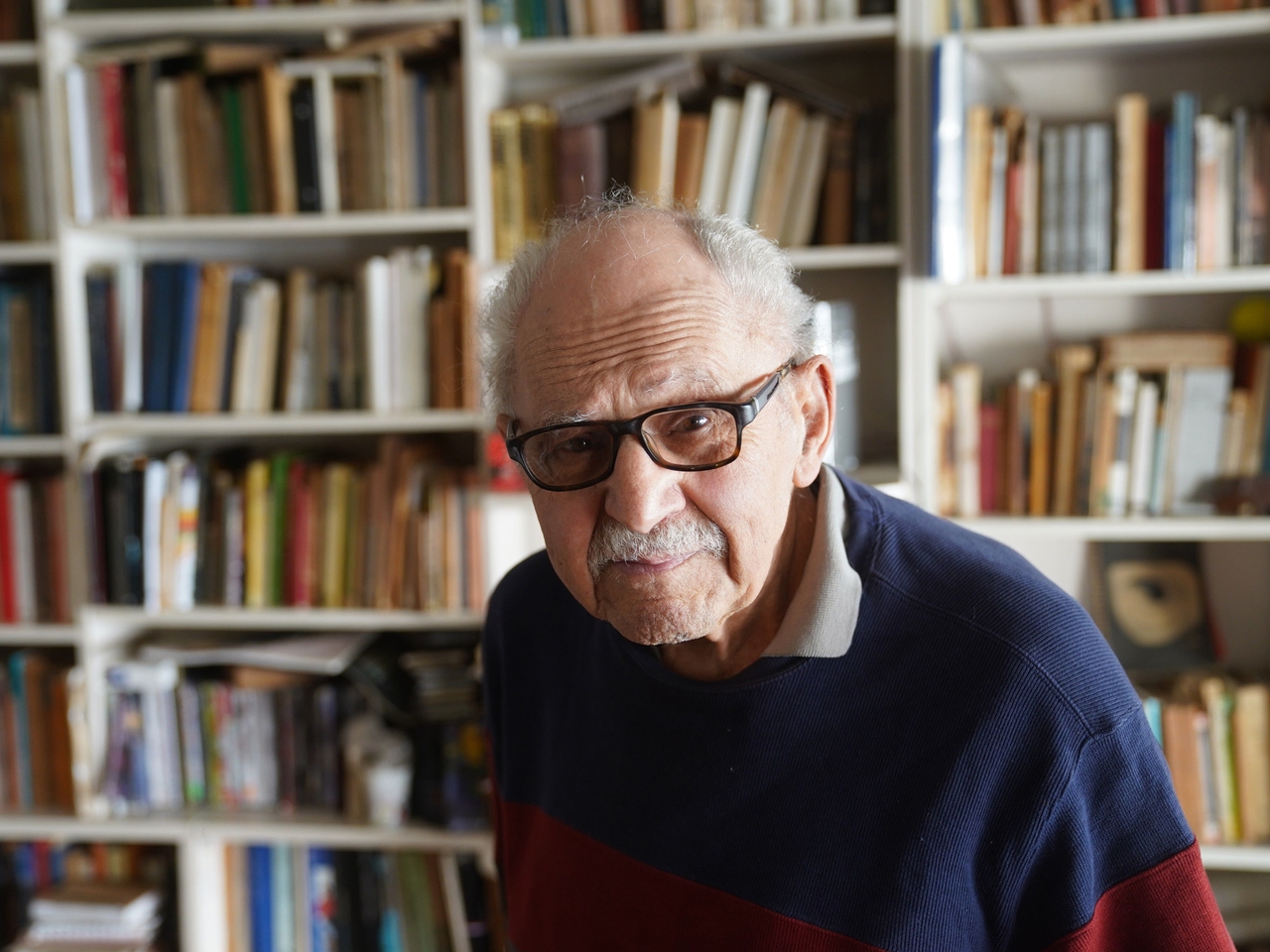

More than seven decades have passed since then, and Halac —a Buenos Aires native, 90 years old, born on Monday, May 13, 1935, a leading figure in Argentine theater—continues to tell stories. He has written more than 20 plays, teaches, directs, and retains that curious air of the boy who once accepted an invitation to the theater. He speaks with Ñ on a mild spring morning at his home in Palermo. The excuse—if one were needed—is his new award: the Ñ Lifetime Achievement Award, which consecrates him, once again, as what he has long been: an indispensable figure in Argentine theater.

Seeing Enrique Santos Discépolo tremble was merely the first act of a vocation that had been developing in other languages. The Halac family were Sephardic Syrians, settled in Buenos Aires, and spoke four languages fluently. French, for example, was used for family diplomacy: when it was time to suggest to a friend that it was time to leave, his mother would say elegantly, “ Tell your friend to leave .” “Syria,” he recalls with the air of a historical chronicler, “was a French colony.” His father and uncles owned a silk shop at the corner of Carlos Calvo and Lima streets.

Playwright Ricardo Halac. Photo: Guillermo Rodríguez Adami.

Playwright Ricardo Halac. Photo: Guillermo Rodríguez Adami.Theater came later, through the library of the YMCA, the Young Men's Christian Association, where he went to play sports. There, Halac discovered Shakespeare and the Greeks. "Theater really captivated me," he confesses. Before, when he was an asthmatic boy who spent long periods in La Falda or Los Cocos—because doctors prescribed dry air—he had found refuge in reading. The doctor had also told him to play sports and live near a park. And so he grew up in the shadow of Rivadavia Park, swimming, playing tennis (he still plays doubles with Esteban Morgado today), and reading incessantly. "All of that turns you into an introverted boy who read a lot," Halac summarizes, with a half-smile. Among his first readings, he mentions two volumes of an illustrated children's Bible, which his father had bought him in his childhood.

During that childhood and adolescence steeped in reading, the playwright and journalist Ricardo Halac was forged, almost without his noticing. At some point, writing was added to his reading. He studied at the Carlos Pellegrini School; then he fulfilled his father's wish: three years in Economics, "because you could get a job quickly." However, at 21, Halac deviated from that path and won a Goethe Foundation scholarship to study theater in Berlin. He went for a year and stayed for two, like someone who forgets to return because he's too busy discovering the world.

But here we must explain why Halac came to the Goethe Institute: Halac came to the Goethe Institute not for theater, but for German. And not for German itself, but for Bertolt Brecht —translations were hardly available, or they weren't good. And he wanted to read Brecht without intermediaries after having seen, in the independent theater, where else, Mother Courage and Her Children , which also starred none other than Alejandra Boero. A whole package that he considered absolutely experimental for the time. In short, a Brechtian jolt : “I was used to three-act theater. And suddenly I saw an experimental play, epic theater, with music, signs that spoke to the audience. That was Brecht, a man who invented. I loved it.” And German left such an impression on him that even today, upon entering his house, one finds a photograph hanging in the hallway: Bertolt Brecht and Charles Chaplin, side by side. So that it is clear which god is worshipped in this temple.

"Solitude for Four" premiered in 1961. Archive photos courtesy of Ricardo Halac

"Solitude for Four" premiered in 1961. Archive photos courtesy of Ricardo HalacThen came everything else: 22 premiered works, three unpublished ones, a single novel ( The Bachelor , adapted for film with Claudio García Satur), five children from three couples – Eva , Martín, Luciano, Marina and Juan –, exile in Mexico due to threats from the Triple A, the direction of the Cervantes Theater, that of the Chagall Cultural Center at the AMIA, the vice-presidency of Argentores (an entity where he still teaches a seminar on dramaturgy today), the awards (Martín Fierro, María Guerrero, Konex) and a whole life dedicated to three professions that feed off each other: dramaturgy, journalism and teaching.

His first play was called *Soledad para cuatro* (Solitude for Four) , and it premiered on October 3, 1961, at the Teatro La Máscara, a haven for eccentric characters, located at the corner of Paseo Colón and Belgrano. Halac was 26 years old. That the protagonists were a certain Agustín Alezzo and a certain Augusto Fernandes (who also directed it) was not merely a stroke of luck. When Halac finished the play, he showed it to the playwright Osvaldo Dragún. Dragún took it to the important Fray Mocho Theater, to which he belonged (he was a communist). The play was debated, as was customary then in the established groups of independent theater. They argued until three in the morning, and in the end, they voted against it. That the play portrayed a negative side of youth. That it wasn't worth staging.

Halac , however, isn't one to back down in the face of a "no." Besides being a playwright, he was a journalist at the newspaper El Mundo , and one afternoon, between writing a story and drinking mate, he ran into two young men in the newsroom who had come in for a story: Alezzo and Fernandes. Halac took advantage of the situation and, as if by chance, gave them the play. Alezzo and Fernandes read it, were enthusiastic, and decided to stage it, perhaps because there were good roles for both of them. "Later they told me it wasn't easy to put it on, that they had to leave the Party because it had been rejected," he says.

The debut was a success. The play was distinguished as the best of the year by the Association of Theater Critics and marked a milestone for the Teatro La Máscara, a venue that revolutionized the Argentine theater scene. Founded in the late 1930s, the theater became a beacon of independent theater, especially from the 1960s onward. It was a space for the renewal of national theater by introducing foreign authors such as Bertolt Brecht and Samuel Beckett to the local conversation. Throughout the interview, Halac repeatedly and passionately emphasizes “the importance of the independent theater founded in 1930 by Leónidas Barletta” (who also created the Teatro del Pueblo). “My first experience was in independent theater, which is unique in the world and which shaped us as a culture.”

Halac waves at the end of a performance of "The Weaning".

Halac waves at the end of a performance of "The Weaning".Although he once dabbled in commercial theater, most of his plays originated in independent venues: from Soledad para cuatro (Solitude for Four) in 1961—which only returned to the stage at the Cervantes Theater in 1999—to Cría ángeles (Raise Angels ), premiered in 2025. And he's already hinting that another one is on the way. "Independent theater is a great asset," he affirms, with the calm that comes from experience. He also says that he never stopped going to rehearsals, that he's still amazed by actors: "Sometimes they know the character better than I do. The actor creates, and the director creates based on that." And he reveals that he was one of the first to do: "Go on stage with an actor and discuss things with the audience."

–What do you remember about the premiere of your first work?

–I remember three things. One, that during the intermission I went out to see my friends and colleagues, those who would later be part of the Generation of '60 and Teatro Abierto, and in a corner were Gorostiza and Cossa. I was anxious and asked them, “So, how's it going?” They answered, “So far, so good. We'll see how it ends.” Secondly, my father had warned my brother Enrique that if he went with his girlfriend, who was a Christian, she would cause a scene at the theater. My brother asked me if I was going with his girlfriend. I said yes.

Open Theater, 1981.

Open Theater, 1981.–And did your dad make such a fuss?

–In the end, no. And the third thing is that the girlfriend I had at the time, who inspired me to write Estela de madrugada , arrived during the intermission, opened the door, looked at me, said she wanted to wish me luck, and left. I don't remember if we had argued or what.

–Then I premiered some works that I love very much. A more romantic period. There's a lot of talk about love; there's Estela de madrugada, Tentempié, Segundo tiempo, Fin de diciembre . I had already gotten married, was living in a two-room apartment, and my first daughter, Eva, had been born.

–Why is she called Eve...?

–Once, when Eva was two years old and I was pushing her in a stroller, a woman I knew from somewhere, who was Jewish, stopped me and said: “How lovely, you named her Eva after the Bible.” And I said: “No, I named her Eva after Evita.” I admire Evita, for her origins, for the rejection she faced, which ultimately made her ill.

–He was part of the so-called Generation of the 60 in theater, a very prolific group that was attentive to social problems.

–They divided us into two groups; on one side, the more realistic ones, those of a more “committed” and “combative” theater, and on the other, those of the absurd or those of “art for art’s sake.” In my group, there were Carlos Gorostiza, Tito Cossa, Carlos Somigliana, Germán Rozenmacher, and Osvaldo Dragún. And then there were Griselda Gambaro and Tato Pavlosky. And the fight between them began.

"The Bachelor" (1977), with Claudio García Satur, film adaptation of the only novel by Ricardo Halac.

"The Bachelor" (1977), with Claudio García Satur, film adaptation of the only novel by Ricardo Halac.–But, beyond this creative clash, what a time, right?

“On top of that, I came from Europe, where it was common to speak ill of others publicly. Camus and Sartre were very close friends, but when Camus died and Sartre was asked about him, he replied, ‘He’s been dead for a long time.’ I dared to criticize Gambaro in a magazine. And we had a falling out. Before, there was an ideology, but today ideology doesn’t exist because ideas have collapsed. But I wanted to change reality.”

–Did you think that theater could help change things?

“Like Ibsen, I saw theater as a tool for change. That’s why he wrote those marvelous plays that made him the greatest in history. Some of those plays are frighteningly relevant today, like An Enemy of the People. Back then, you could see the reality that was coming. Now I don’t see anything good. Some say a world war is coming. I live in a country that has never experienced violence due to conflicts between the Abrahamic religions: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam have coexisted here. At the end of the 19th century, something very strange happened in France: Dreyfus, a Jewish French officer, was accused of spying for Germany. He was convicted. The writer Émile Zola came to his defense and created an enthusiastic movement that secured his release. The figure of the committed intellectual emerged, whose opinion was politically valid. The intellectual began to see and consider himself differently.”

–What's happening with that role today?

"For a long time it continued. But then the war broke out and the United States emerged as a great power. There, too, intellectuals proliferated. But the House Un-American Activities Committee began imprisoning writers and cultural figures. Arthur Miller said he was harassed in the street, and that's why he wrote *The Crucible *. But the theory that art is amusement , entertainment, gained traction, promoted especially by the major film studios, which dominated the Western world and made enormous profits from that theory. It's very difficult to break free from that. Today, that role of the intellectual is over."

"Because the messianic ideology, which was communism, collapsed under its own weight, due to its own mistakes. You might say it was always under attack from capitalism, or whatever, but it collapsed because of its own errors, it fell into dictatorship. When I was young, I visited many communist countries: East Germany, Yugoslavia, where Tito was, which was a different experiment. Later, I went to teach in Cuba several times. That system doesn't work; it has several flaws, and it ends in horrible dictatorships. So, that ideology is in crisis and hasn't been replaced by another. I would say that we are living, at this moment, the end of an era in the world; I don't know if it's the fault of individuals, because, as Marx says, there are also forces that move on their own."

Ricardo Halac with Luis Brandoni, star of the play "Second Half".

Ricardo Halac with Luis Brandoni, star of the play "Second Half".–He is one of the founding members of Teatro Abierto, in 1981. What was that experience like?

“We were living under a dictatorship, and we decided to do something. The subject of Contemporary Argentine Theater had been removed from the Conservatory of Dramatic Arts. And, around that time, Kive Staiff, then director of the San Martín Theater, was asked why there were no Argentine playwrights in the theater season, and he replied that ‘they didn’t exist.’ That hurt a lot. Suddenly, 20 playwrights got together and created shows with complete freedom in short formats. We secured the Teatro del Picadero. And I wrote a play that I really like, called Distant Promised Land .”

–And one early morning they set fire to El Picadero.

“We were all in a very bad way, but we decided we were going to continue. For the dictatorship, burning down our theater was a mistake, because something that belonged to a few authors became national. We held a conference attended by Borges and Sabato. We said we would continue. Romay offered us the Tabarís. We filled it nonstop.”

–He also did television programs such as Stories of Young People, The Night of the Great Ones (directed by David Stivel on Channel 7), Commitment and even won the Martín Fierro award with I Was a Witness.

"Compromiso was a resounding success. Then Alfonsín came to power, and we moved to Channel 9 with 'Yo fui testigo' (I Was a Witness), a program where we discussed Argentine history. There was a fictional segment, and we always interviewed people who had some connection to the topic at hand. I was the first to talk about Eva Perón on television. Later, I did a program that caused me problems with Cuba because it questioned the figure of Che Guevara, especially his campaign in Bolivia. I was teaching, and at one point, my classes were suspended; but at that time, I was the director of the Cervantes Institute, and they didn't dare fire me. Because censorship is rampant in all communist countries. But it doesn't exist anymore. We have to wait for another utopia to appear. Humankind needs a utopia to live."

Virginia Lago and Víctor Laplace in "Distant Promised Land", for Teatro Abierto.

Virginia Lago and Víctor Laplace in "Distant Promised Land", for Teatro Abierto.–He was the director of the Cervantes National Theatre between 1989 and 1992.

“I was director of the Cervantes Theatre during a very dramatic time in my life, because I couldn't do anything; I had no budget. It was the Menem era, and I had 200 employees. It was madness to have accepted. Then I left, and the owner of Konex, who was very fond of me, approached me and offered me the opportunity to create a cultural center for the AMIA Jewish community. I developed the programming for the Chagall Cultural Center, which was partly Jewish and partly Argentine. I organized meetings with politicians every week, and we discussed the current situation. Néstor Ibarra, Félix Luna, Marcos Aguinis. We continued even after the AMIA bombing.”

–The Judeo-Spanish trilogy came into production.

“I ran into an actor on the subway who was on the San Martín committee that decided which plays to program. He asked me if I had any. I always have several. I had one half-finished, which is A Thousand Years, One Day (1993), which tells the story of the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492. I studied the subject extensively. For the Jewish community, culture has a very special value. The thing is, the play requires about 45 actors on stage. Even so, they took it to the San Martín, and Alejandra Boero, who had awakened my vocation when I was 17, ended up directing it.”

"It's a strange way to see it again. It premiered with 45 characters and was one of the San Martín's biggest hits. It was packed for four months, every single day. And I would go and watch the audience applaud. Later, they tried to stage it in the United States and Spain, but there was the problem of the number of actors. Then, I did a version with 12 characters. This play was the basis of the Judeo-Spanish trilogy, along with * La lista* (2016) and *Marcados, de por vida * (2022), the latter about the converts under the Spanish Inquisition during the Golden Age. I love all three of them very much. Because of my age, I knew what it was like to be Jewish before the State of Israel existed. I remember once, when I was 10, seeing the photos of the Auschwitz ovens. My father started to cry. I'll never forget it. He grabbed my arm and said, 'Ricardo, we always have to be prepared, because at any moment we might have to leave.' That phrase marked me." Why did I have to leave? What had I done to deserve such a sentence? That's how the trilogy was born, written many years later. I remember the day my father bought a desk for me to study on and placed a map under the glass: "So you'll have it in mind." It was a map of Israel.

Ricardo Halac, as a journalist, with Ringo Bonavena.

Ricardo Halac, as a journalist, with Ringo Bonavena.–You can see his journalistic streak.

“I always loved being a journalist. I started at the newspaper El Mundo , in the cultural section. I wanted to sit at the same desk as Roberto Arlt, so I would sit at each one for a day because nobody remembered which one I had occupied. One day the editor called me and told me that there was an American organization, The World Press, that chose ten journalists a year to travel around the United States. And it turned out I was chosen.”

–Did the two roles coexist: playwright and journalist?

–The alliance between journalist and playwright is very important. You can't stop working; I keep writing. Rest? I rest by writing, if I write what I like. Luckily, I've never had to write anything I didn't like. When Soledad para cuatro premiered, a colleague at the newspaper gave me a scathing review. I remember the editor calling me and saying, "Look, Ricardo, we appreciate you a lot, but we're not going to publish it." She hadn't liked it because the characters addressed each other as "vos" (the informal "you" in some Latin American countries); it's one of the first plays to use "vos."

Halac began his career as a journalist at the newspaper "El Mundo".

Halac began his career as a journalist at the newspaper "El Mundo".–How did you get to La Opinión , Jacobo Timerman's newspaper? There you worked in the cultural section under the direction of Juan Gelman and with colleagues such as Osvaldo Soriano, Paco Urondo, Tomás Eloy Martínez, Horacio Verbitsky and Carlos Ulanovsky.

“There was a reader who was delighted with my articles in the newspaper El Mundo. It was Jacobo Timerman, who, with the help of Horacio Verbitsky and others, was putting together the first editorial team of La Opinión. He contacted me. They commissioned me to write the cultural supplement. I have very fond memories of that time. The supplement was wonderful. Once, Gelman asked me for an article on Brecht and put it on the cover with an illustration by Sábat. The newspaper was a huge success. And the supplement, especially, was a huge success. Gelman would call me to his office while he was writing poems, and I would read them to him. It was a very beautiful time. My journalistic career continued. I wrote for La Nación for four years. And also for the magazine Florencio , published by Argentores.”

–Did you know Rodolfo Walsh?

"I saw him at several meetings; he was a very intelligent man. Like Soriano, like Urondo, a great poet. Urondo made a mistake one day when he came to the newspaper office, which was located on the corner of Reconquista and Viamonte streets. He left his car on a corner and it was rear-ended. The trunk lid flew open and it was full of weapons. That's when he went underground."

–What other personalities did you meet as a journalist or playwright?

–On my trip to the United States, I interviewed Martin Luther King. And, in the 80s, Arthur Miller visited Buenos Aires. There was a meeting with actors and playwrights. He talked for about three hours. He was very down-to-earth and generous. Because the idea is precisely to inspire others.

Clarin