More women get Alzheimer's than men. It may not just be because they live longer

Working three full-time jobs, raising kids and tending her blooming garden: Angeleta Cox says her mother, Sonia Elizabeth Cox, never really slowed down all her life.

Then, at the age of 64, a diagnosis of Alzheimer's slammed the brakes on the vibrant life she'd painstakingly built after immigrating to Canada from Jamaica in 1985.

"The onset of the symptoms came on very fast," Cox said of her mother.

"She forgot my dad first, and she wasn't able to respond to my brother, so I became a care provider for her," said Cox. Sonia Elizabeth died late last year, after years of battling Alzheimer's.

More women get diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease than men. In developed countries, studies suggest about two-thirds of people with Alzheimer's are women. It's a pattern seen in Canada, too, where women account for almost two-thirds of people with dementia, according to the last count from Statistics Canada.

Scientists long explained this with a simple demographic fact: women tend to live longer, and age is a strong risk factor for the development of dementia.

But that understanding is now changing.

While age is still considered an important risk, scientists are increasingly realizing other aspects — both biological and sociological — may play an important role in making women susceptible to developing Alzheimer's.

"I think we're beginning to be at an inflection point," said Gillian Einstein, who studies how sex and gender can influence an individual's risk for developing dementia, as part of the Canadian Consortium on Degeneration and Aging.

"I think you can feel it here," she said, gesturing around at the Metro Toronto Convention Centre, where leading Alzheimer's researchers gathered for the annual Alzheimer's Association International Conference (AAIC) in late July.

"There's so many more sessions on sex differences, or women's health."

Hormones, babies and menopauseAlzheimer's disease is the most common form of dementia in the world, according to the World Health Organization. It causes symptoms like memory loss, confusion and personality changes. In Canada, Alzheimer's is also the ninth leading cause of death, according to Statistics Canada.

One factor scientists now know about: the timing of key hormonal changes, like when women first get their periods, how long they are fertile for, and the age they reach menopause.

"There are a lot of studies in the UK Biobank, for example, showing that the longer the reproductive [period] women have, the lower the risk is of late-life Alzheimer's disease. Having [one to] three children also seems to lower the risk of Alzheimer's," said Einstein, referring to a large database containing the health and genetic information from 500,000 volunteers.

Premature menopause, which happens before the age of 40, and early menopause (between the ages of 40 and 44) are also key risk factors, said Dr. Walter Rocca, who studies the differences in the way men and women age at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

"So these women should be treated appropriately to avoid these deficiency of hormones," said Rocca, who presented research on the topic at the AAIC conference.

What that treatment looks like could vary widely, Rocca said, based on the patient, as well as the cost and availability of the drug. Some main treatment approaches include pills, patches, gels and creams containing the hormone estrogen, which has been shown to have neuroprotective effects but naturally declines during menopause.

The risk of cognitive decline with early or premature menopause exists whether the menopause happened naturally, or caused by their ovaries being removed, says Einstein.

She pointed to a study she co-authored, which analyzed data from over 34,000 women from the UK Biobank.

"Women who had their ovaries removed prior to the age of 50 will also have an increased risk of Alzheimer's," she said.

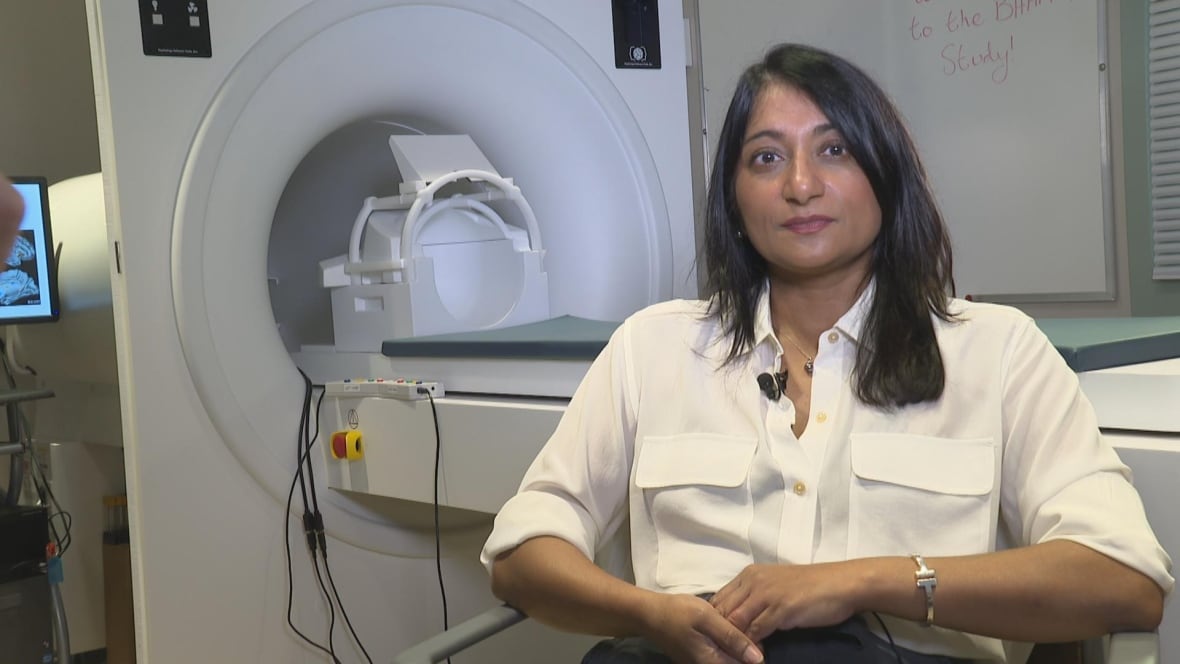

More inclusive researchResearchers are playing catch-up, when it comes to understanding women's risk for Alzheimer's, says Natasha Rajah, a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Sex, Gender and Diversity in Brain Health, Memory and Aging at Toronto Metropolitan University.

"Not only have we not been included in the research, but even in the clinical trials, we're not represented," she said.

"It makes no sense when you think this disease affects more females than males."

She's hoping to fill in some of those blanks. She's currently conducting the Canadian Brain Health at Midlife and Menopause study (BHAMM), which searches for early signs of the disease through brain scans and blood samples at mid-life.

"We're trying to understand whether or not menopause is a window at which some females might be showing early signs of Alzheimer's disease," she said.

If they are identifiable, those showing early signs of disease could get treatment or alter their lifestyles to better age, according to Rajah.

There is no cure for Alzheimer's, but treatments include drugs that can help manage symptoms. Lifestyle changes, like physical exercise and a brain-healthy diet have also been shown to help brain health in older adults at risk of cognitive decline.

She's also hoping to capture a more diverse population group in her research to better understand risk factors associated with race. Alzheimer's research in Western countries like the U.S. and Canada hasn't always been diverse, says Rajah.

"With the BHAMM study, we're trying to reach out to as many communities as possible because we want to be more representative in our research."

Different choicesLooking back, Cox says she now realizes surgically induced menopause was a risk factor for her mother, who had a full hysterectomy after having fibroids in her 30s.

The knowledge has led her to make different choices for herself — like reducing stress and taking care of her mental health.

She's also now aware of how her own hormones can interact with Alzheimer's risk.

"When it came time for me to deal with my fibroids that I had, I chose not to have a full hysterectomy."

She's also passing down the knowledge to her daughter — and sharing it with other members of the Black community who have been impacted by Alzheimer's, through the Pan African Dementia Association. She's hoping researchers will find out more about risk factors for women developing Alzheimer's — so fewer women and families have to live through what her mom did.

"When it impacts women, it impacts the entire family and the community," she said.

cbc.ca