What truth for the polis?

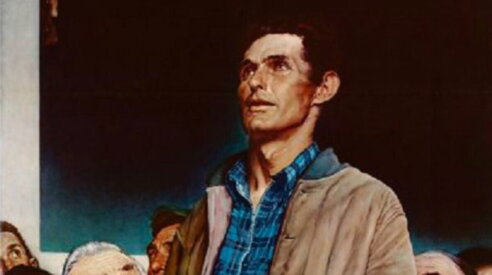

Norman Rockwell's "Freedom of Speech," published in the Saturday Evening Post, February 20, 1943.

What is truth? /3

Thus, post-liberal thinkers rebel against the "weak gods" of the open society. But there's a misunderstanding: Popper doesn't theorize about a "wide-open" society. Fighting authoritarianism without giving in to relativism

On the same topic:

Flavio Felice is a full professor of History of Political Doctrines at the University of Molise. His article continues Il Foglio's summer series dedicated to truth. Each week, a different author will examine this fundamental concept from the perspective of a specific discipline: law, mathematics, astrophysics, economics, politics, information, or theology. " Truth, in Practice" by Michele Silenzi was published on July 15th, and "Truth in the Bar" by Giovanni Fiandaca on the 22nd.

Does it make sense to talk about truth in politics, or does the "effective reality" by which politics is measured have nothing to do with truth? And yet, does talking about truth in politics imply an instantaneous slide into moralism? Well, I wonder if these questions are crucial and unavoidable ones that people everywhere have always pondered, or rather idle problems, "selfishness dressed up in sophistries." Perhaps both answers are true, and the fate of the entire discussion hinges on what idea of truth we cultivate when we move in the realm of politics. In this regard, it is necessary to immediately clarify that, in this specific field, we are dealing with moral convictions and the search for practical truth, whose methods of investigation are as different from theoretical as they are from scientific certainty.

The very moment we ask ourselves the question of truth, we expose ourselves to the risk of being trapped in the cage of fundamentalism, of being pigeonholed into the category of those who, in the name of their own subjective worldview, claim to standardize what can be standardized. And the stronger the truth recognized and proposed, the greater the risk of being "opposed, mocked, and despised" or, at best, as Pope Leo XIV stated in his first homily to the cardinal electors last May 9, "tolerated and pitied."

On the other hand, how can we deny that, in the name of some truth, the worst atrocities in history have always been committed, and that, in the name of a vaunted truth, so many have been denied their dignity as human beings. Here comes a highly topical issue, one that is particularly hotly debated throughout the West and especially in the United States, where proponents of liberal democracy, both classical and progressive liberalism, are pitted against the theorists of so-called postliberalism, who have a firm point of reference in Patrick J. Deneen of Notre Dame University. The two liberal traditions are practically polar opposites, but, in the specific context of the debate over the future of liberal democracy, classical liberals and progressive liberals appear increasingly surrounded and threatened by postliberalism and united by the need to defend and continue to promote the principles of the "open society," even though the two traditions differ on some important aspects. as essayist N.S. Lyons (a pseudonym), the author of The Upheaval, a Substack newsletter, wrote: “For eight decades now, the old elite, both left and right, have been united by their common priority of the open society and its values.”

Lyons's essay, "American Strong Gods. Trump and the End of the Long Twentieth Century," published February 13, is an interesting and controversial contribution to the debate, helping us understand how the question of truth—among heated passions, the hottest imaginable—still represents a crucially important issue in politics. Beyond endorsing Lyons's theses, I believe it is useful, especially for proponents of the open society like myself, to delve into the heart of the arguments of those who today theorize the definitive decline of the dream of an open and global society. Postliberal theorists envision a closed, communitarian society, and for this reason, in their view, a society with greater internal solidarity, imbued with strong values and heated passions for which people would be willing to sacrifice even themselves. A decidedly more solid society, therefore, because it is protected by "strong gods," compared to open societies presided over by "weak gods."

Lyons's reasoning is based on a historical consideration: the spirit of the 20th century, in the wake of the horrors of the Second World War and the totalitarianisms that accompanied it, was characterized by a "never again," embraced by Western political and cultural elites, towards the strong values that had sustained the totalitarian abomination. A "never again" that, however reasonable and understandable, transformed into a "totalizing obsession" that ended up denying any strong passion and moral yearning aimed at the search for truth ; resorting to Michael Freeden's morphological interpretation of liberalism, we are faced with the fifth temporal layer (M. Freeden, Liberalismo, Rubbettino, 2023). The main defendants in this hypothetical trial of the open society are Karl Popper and Theodor Adorno , guilty of having convinced the post-World War II establishment that the main cause of authoritarianism and totalitarianism was the "closed society." Here comes into play another author of great importance in the American public debate, the theologian Russell Ronald Reno, currently director of the influential magazine First Things, founded by Father Richard John Neuhaus, who, together with Michael Novak and George Weigel, ironically, contributed significantly to opening the social teaching of John Paul II to the demands of classical Anglo-Saxon liberalism and to that peculiar strand of American social thought that Novak used to define as Catholic Whig.

In a 2019 book, The Return of the Strong Gods: Nationalism, Populism, and the Future of the West (Regnery Gateway), Reno defines this ideal of a "closed society" as that particular type of society characterized by so-called "strong gods"—that is, strong beliefs and truth claims, strong moral codes, strong relational bonds, strong community identities, and ties to place and the past; ultimately, Reno writes, all those "objects of human love and devotion, the sources of passion and loyalty that bind societies together."

At this point Reno and Lyons agree that, in the aftermath of the Second World War, a culture particularly hostile to such strong passions had spread, deemed dangerous as they were considered the basis of fanaticism, oppression, hatred and violence: faith, family and nation, essentially the equivalents of our own "God, country and family", were considered suspect and judged as the forerunner to the return of immortal fascism.

At this point, in place of the "strong gods," deemed dangerous and, for this reason, worthy of expulsion from the liberal-democratic citadel, appear the so-called "weak gods," such as tolerance, doubt, dialogue, equality, and consumerist well-being. These are elevated to the role of defenders of an open society, as promoters of a political, economic, and cultural system capable of opening minds, relativizing truths, and weakening bonds. In short, communities such as families, churches, and nations are nothing more than tribes, and strong ideals are nothing more than the remnants of a tribal culture from which it has become necessary to distance ourselves to avoid the eternal descent into the abyss of fascism .

To conclude this brief exposition of positions so radically hostile to the open society, it is worth noting that the core of the post-liberal proposal calls into question three cornerstones of liberal democracies: the progressive dismantling of borders and the consequent deconstruction of the notion of national sovereignty; the consolidation of post-ideological functionalist politics; and the hegemony of the liberal international order. The most interesting aspect of this radical right-wing critique of the notion of the open society, and one that highlights a certain irony, is that it is also partly shared by a certain left and by those currents of thought that attribute to neoliberalism, whatever that may mean, responsibility for all the atrocities of the last eighty years .

With a proud and satisfied tone, Lyons asserts that the dream of the "open society" has not come true, for the simple reason that "the strong gods refused to die," and today we are witnessing the return of archetypes such as the "hero," the "king," the "warrior," and the "pirate." All figures that deny the very foundations of the "collective suicide pact of Western liberal democracies." He concludes: "Today's populism is more than a simple reaction to decades of elite betrayal and poor governance (although it is also that); it is a deep, repressed, and tumultuous desire for long-delayed action, to break free from the suffocating lethargy imposed by procedural managerialism and fight passionately for collective survival and self-interest."

It's clear that the great enemy of this strand of the American right that opposes the open society and liberal democracy, even before the left, is precisely that neo-conservatism that has fully embraced the principles of the open society. The great enemy is the cuckservative, a weak conservative, although the literal translation is far more insulting. As a dear American friend explained to me, the cuckservative is a conservative willing to let others do as they please; in short, a conservative who, in words, says he is against the left, but then, in practice, supports it.

At this point in the discussion, we can attempt to draw conclusions and return to the theme of truth in politics from which we began. Postliberalism presents a caricature of Popper's open society, whose critique, it is worth remembering, is oriented towards positivistic rationalism, acknowledging the liberal West's debt to Christianity. On this point, I refer you to Dario Antiseri's work, Karl Popper. Protagonista del secolo XX, Rubbettino, 2002. The Viennese philosopher certainly presented the open society and liberal democracy as incompatible with dogmatism.

However, following a path quite similar to that taken by Norberto Bobbio , according to which there is an irrepressible question that arises within man every time someone pronounces the sentence "God is dead," Popper does not crush the open society into the terrain of skepticism and, on the moral level, he does not at all believe that moral norms should be repudiated, but rather criticized and debated , since no one is given the right to set themselves up as a magistrate of ideas. In this sense, the true enemy of Popper's open society is the absolutist pretension that potentially unites both progressives and reactionaries, in the name of exclusive knowledge of a hypothetical direction of history, and not the presence of strong passions that have the merit of animating discussion in the public arena.

Contrary to what post-liberal theorists claim, Popper's liberal democratic principle is justified by the fact that the institutions of an open society allow for the coexistence of a plurality of ideals within the same community; one could say that the same people who recognize themselves as members of a community retain their dignity as free persons. Thus, the justification of an open society and liberal democracy, as Rocco Buttiglione writes in Sulla verità soggettiva. esiste un alternativa al dogmatismo e allo scetticismo? (Rubbettino, 2015), appears to be a consequence of the personalist principle, whose connection to the Christian tradition is indisputable . Furthermore, Popper's open society, as Antiseri has written, is anything but a "wide-open" society, lawless and anarchic, but rather a society in which norms can be subjected to rational analysis that allows for a peaceful process of revision of the norms themselves, proceeding through trial and error: problems, conjectures, refutations. In short, Popper's polemical aim is not the search for truth, but rather the claim that it can be deduced once and for all by reason, going beyond that limit that would project it into the realm of totalitarian reason. So, returning to the question we started with: does it make sense to talk about truth in politics? We can only answer by specifying the type of truth we're referring to when we handle political matters .

Since we cannot pretend to impose on any field of knowledge a degree of certainty higher than its proper one—a sort of epistemological subsidiarity—we are also not authorized to impose on the political field a certainty that derives from another field, be it scientific or religious. In short, we cannot reduce political decisions either to (always relative) scientific certainty or to (subjective) religious certainty. Political decisions are formed on the basis of the method that is proper to politics: critical discussion, the constant exchange between free and responsible consciences .

Practical truth, the kind of truth that concerns the realm of politics, is a certainty that derives from the option closest to our idea of truth, the one that assumes the greatest degree of probability (verisimilitude), in a given situation in which the choice is forced upon us, no longer postponable. From this perspective, truth is first and foremost an encounter ; the encounter with reality and with the other who defines its contours, mortifying the pharaonic spirit of omnipotence; it is an encounter with the person of the other, with their highly personal certainties, doubts, and passions; it is an encounter that occurs in a specific time and place and takes on the quality of that specific time and place. Buttiglione writes: "What does not happen in the present moment may happen at a later moment, and those who truly love the truth should avoid making it hateful by violently imposing an insincere assent."

Recognizing the relative quality of practical or moral truth reveals the pitfalls that have always threatened homo democraticus and highlights the importance of those "invisible geniuses" – philosophy, philology, history (Enzo Di Nuoscio, I geni invisibili della democrazia. La cultura umanistica come presidio di libertà, Mondadori, 2022) – that serve as sentinels stationed on the ideal bastions of the democratic citadel, which, by definition, is an "open" place, therefore, in fact, exposed to the threats of its many enemies. Saint Augustine's famous maxim: " In te ipsum redi, in interiore homine habitat veritas " (Return to yourself, the truth dwells in the inner man [De vera religione, XXXIX, 72]) tells us that practical truth, that which concerns the field of politics, traverses the times and places of life, is embodied in the encounters we have, in the people we love, and in the mistakes we make; it is so true because it concerns me, and me alone, and it is so relative because it can evolve and unfold in an increasingly authentic way thanks to the encounter with the other.

More on these topics:

ilmanifesto