The truth, in practice

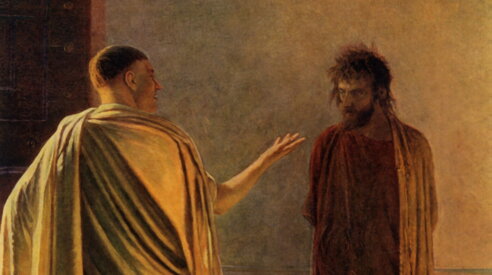

Nikolai Ge, “What Is Truth? Christ and Pilate,” 1890, oil on canvas. (Photo by The Print Collector/Getty Images)

What is truth? /1

The concept that reveals the incandescent core of the relationship between man and the world, the line separating Jesus from Pontius Pilate. Postmodern skeptics, these articles on truth are for you. Episode number one

On the same topic:

Il Foglio's summer series dedicated to truth begins with an introduction by Michele Silenzi. Each week, a different author will examine this fundamental concept from the perspective of a specific discipline: law, mathematics, astrophysics, economics, politics, information technology, or theology.

“Quid est veritas?”, what is truth? This question, among the most famous in human history, was uttered by Pontius Pilate, addressing Jesus. Christ remains silent before this question, providing no answer because he had already provided the answer in an enigma as blinding as the broad light of day: “I am the way, the truth, and the life.” I am the truth, that is, the word made flesh: the presence, the direct manifestation of that about which one could otherwise do nothing but remain silent (as Wittgenstein would suggest two thousand years later) .

Between Pilate's reasonable, skeptical question and Jesus' enigmatic statement lies the entire game that revolves around a questioning of this all-encompassing yet entirely debased term, "truth," which is nevertheless integral to our relationship with the world. Yet, in speaking truth, we are still in Pilate's situation. What is it? Can we seek a stable definition of this concept? Or is it nothing more than the guiding principle that must accompany us in its constant and tireless pursuit? Or, again, is it a term essentially devoid of meaning?

In philosophy, what is called the "history of metaphysics" could also be defined as a history of the search for truth, that is, for something certain beyond all doubt, on which we can definitively base the entire apparatus of our knowledge and, why not, even our salvation.

Last summer, this newspaper promoted a series of philosophical articles reflecting on the theme of metaphysics , a concept now obsolete yet fundamental to understanding the entire course of Western history. This year, we thought it would be interesting to propose an even more radical series, going directly to the source of the spirit of inquiry that characterizes humanity . This source is enshrined in the word "truth" (in its presence, its absence, its possibility).

The contributions will span diverse disciplines that, in different ways, relate to the search for truth, attempting to understand whether there is a common denominator that can be defined as "the Truth," or whether we can only attempt to approximate it, to approach it, through a variety of approaches. However, it is necessary to clarify a crucial, simple fact that is often overlooked: the search for truth essentially determines all areas of human inquiry . In this series, we will attempt to observe it through jurisprudence, mathematics, astrophysics, economics, politics, information technology, and theology. This article attempts to provide a brief introductory framework for the series.

There is no human dimension that does not somehow, more or less consciously, intertwine with the search for truth. We can say that truth is inherent in the entire existence of each person; it is what concerns us most: the truth about ourselves, about our tastes, about what we want, about what there is in life, and, possibly, after that, about the meaning of what we do. Obviously, the question of truth did not begin with Pilate, but long before. It began, in fact, at the same time a self-conscious individual began to ask questions about the world around him. We can say, reasoning by exclusion, as is inevitable when dealing with seemingly abstract topics (which in reality are the most concrete because they pertain to our relationship with the world), what is not meant by truth here. Truth is not objectivity . That is, it is real and objective that water is composed of hydrogen and oxygen, that bodies are heavy, that the sun emits radiation. All of this can be ascertained, verified, and tested. It is so and not otherwise. It pertains to quantifiable characteristics of real objects.

Truth, however, as we attempt to understand here, is something that has to do with man, with his knowledge of the world, with his action upon it, with it, and "against" it. From this perspective, truth is the revelation of the essential and incandescent core of the relationship between man and the world. As the great Kojève writes: "Without man, being would be mute: it would exist, but it would not be the truth."

It should be clear, therefore, that the search for truth, being an entirely human event, is always a historical occurrence, because everything man does generates history. This means that this search does not occur in the same way across centuries and millennia, but is accompanied by the historical conditions in which man gradually finds himself. In this way, the history of the search for truth is one with the history of civilization. Truth, therefore, is not a fact, that is, something defined that is handed down to us and about which we can speak clearly and distinctly. Nor is truth a saying, a statement. As already seen, Jesus says of himself, "I am the way, the truth, and the life," but remains silent in the face of Pilate's "analytical" question . It is, in fact, his historical existence, the historicity of his own manifestation (his life), that he identifies as revelation, as the truth, as the path to follow.

Moving away from Christianity and turning to a large part of Western thought, which is still shaped by or in opposition to the Christian message, we could say that "truth is a process," that is, it is the ever-changing and evolving totality of world events in which man becomes increasingly self-aware and active. This totality constitutes the "history of truth," of its search and its manifestation. Truth, therefore, is not a quantification, an infinitely precise cataloging of things. It is not achieved through the quantitative accumulation of data, but is an action on the things of the world, on entities, to use philosophical language, to bring them to show us what they "actually are." However, it is a blind, tentative process, in which we seek without knowing what we are seeking. We discover by acting.

This concept, which seems rather abstract, becomes quite evident if we think about our lives, each of us's lives. Our lives are, in fact, for each of us, the most real and concrete thing there is. Yet we can say that it is complete and fulfilled (regardless of the positive or negative outcome), that is, that it has truly become itself, only when it can be seen in its entirety, in its totality, that is, once it is concluded, as the result of a process that has no end except in its own end. At the same time, however, each moment of life, while we live it, is true in itself, in its specific determinacy, but it takes on its overall meaning only within the context of a whole life. Which, however, to be truly fulfilled, must have been realized in freedom .

Trying to sketch a first definition of what interests us, we could say that every entity, everything that exists, has its own truth in the manifestation of its own power, that is, of what it can be. By historically manifesting its own power, or if you will, its own potential, every entity becomes what it is, displays its own truth. But this self-manifestation is nothing other than action. Truth therefore reveals itself as a practice, or rather, truth is achieved only through a practice of liberation (the fundamental relationship with freedom!) from one's own power . In this way, we also understand (although this requires much more in-depth exploration) the close relationship between truth and freedom.

Here, however, suffice it to say that the necessary connection between truth and freedom demonstrates the irreducibility of truth to quantification. If, in fact, the entire potential of beings were calculable and verifiable, there would be no room for events, for the unexpected, for choice, for action. Everything would simply be reduced to a vast array of variables combined and resolved by enormous computing power. Everything would be foreseen and predictable, and therefore there would no longer be events, but only known and enunciable facts.

This, however, should in no way mean a rejection of the quantitative sciences. Quite the opposite! Through mathematics, we know that the world responds to us, that we can understand its physical structure. Einstein, like many others throughout history, wondered how mathematics, being, after all, a product of human thought, was so admirably suited to investigating the physical world, the objects of reality. And the answer lies in the fact that there is a correspondence between thought and being, that what the world is responds to our action, to our doing. Again, Einstein, with his formula E=mc2, tells us nothing more than that matter is energy ready to be transformed to unleash its potential, its power, its truth.

As should be evident by now, from this perspective, the discourse on truth is nothing other than a discourse on humanity. It is, in fact, humanity that draws truth from its hiddenness, to use Heidegger's words, although it would be more correct to say that through their own actions, humanity realizes truth, makes it possible. In this sense, humanity acting freely is the condition of possibility for truth. Truth, in fact, can be conceived historically only through individuals (and not through the mythological "humanity in general") who, in various eras, determine it, think about it, and seek to realize it according to the specific ways of the era and through their own initiative. By realizing the potential of their own lives, they also realize a fragment of truth in their own era. The greatest of the great navigators, Ferdinand Magellan, the man Stefan Zweig portrayed with the force of a modern Ulysses, contributed as much to the history of truth as Einstein: each in his own era and according to his own means . Man is the place where truth is realized and manifested, where things reveal themselves for what they are. Man, in this sense, is a living truth that becomes reality, and thus allows truth to unfold.

Until now, however, over the millennia, the relationship between thought and being, between man and the world, has always been mediated by a mythical/sacred/religious structure concealed by what René Girard called "misrecognition" (the unconsciousness of this mediation). This structure is now irremediably lost. Man now faces the world as one who knows there is no other way to attain truth, that is, to unleash the full potential of all possible energy (or the potential contained within any entity, if "energy" may seem too technical/scientific), than through his own action. It can also be said that this path of liberation, which is also the attempt to historically realize truth, is "man's mission." Although the term "mission" may sound religious—and perhaps it does, because it is with truth that religion has always been concerned—in reality this mission is something terribly concrete. There is no doubt, for example, that Elon Musk (although we may like him less), like Magellan and Einstein, creates a piece of the truth of our era, just as there is no doubt that in our era truth occurs in technology: there it manifests itself and finds its unfolding in the contemporary world .

In the discussion of truth outlined thus far, many points remain unanswered, but only one can be briefly touched upon here: the relationship between ethics and truth. Speaking of human action as the place where truth finds its revelation, can we conceive of the existence of an ethic that should guide us in this "mission" of ours? Is there a scale of values? Is there, in this regard, a moral judgment? Is there a limit to our actions?

A twentieth-century giant, one who contributed to the history of truth, John von Neumann , father of the computer, the H-bomb, and many other achievements, believed it unethical for man not to do, at a scientific/operational level (here we would say in the search for truth), what is possible, despite the destructive potential of each new discovery. From this we can conclude that if the search for truth is one with man's mission, then such a search becomes the only possible ethical stance, the only authentic rule that can guide us.

More on these topics:

ilmanifesto