Rovelli's superficial attack on Enrico Fermi, in which facts bend to ideology

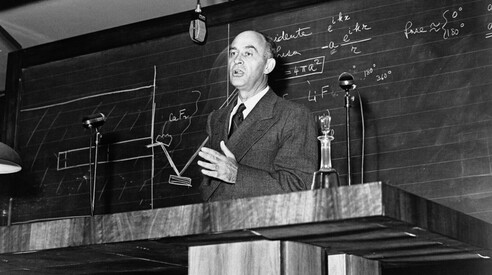

Getty Images

the controversy

In his video for the anniversary of Hiroshima, the Italian physicist and essayist turns a complex historical issue into a petty polemic. The focus isn't on the bomb, but on the Nobel Prize-winning scientist, reduced to the symbolic target of a moralizing narrative.

On the same topic:

It is a real shame that a reflection on the relationship between science and technology and in this specific case between physics and the atomic bomb It was reduced by Carlo Rovelli , in his video for the Corriere commemorating the anniversary of Hiroshima, to a petty polemic in which ideology trumps facts . To the point of provoking an indignant reaction in the world of Italian physics, expressed through its president, Angela Bracco. More than the atomic bomb, Rovelli seems to have Enrico Fermi in his sights , undoubtedly one of the most brilliant physicists of all time, founder of the school on Via Panisperna, which for decades gave Italy an important leadership in the world of physics. Rovelli recalls that Fermi was a member of the Fascist Party, forgetting to add that he had to flee to the United States after the enactment of the racial laws because he was married to a Jew. Rovelli also questions Fermi's merit in winning the Nobel Prize for the discovery of two elements that were thought to be new, but were not. However, the most important reason was his discovery of the effectiveness of slow neutrons in triggering nuclear reactions, a fundamental step toward modern nuclear physics and the nuclear reactor . Another object detested by our man. Why? Trying to demonstrate that the discovery of nuclear fission was an act of arrogance that led to the atomic bomb. Naturally, American arrogance.

Any discussion of the atomic bomb should, instead, be contextualized within the historical period in which it all occurred, to explain its causes, without giving in to facile moralism and displays of intellectual disdain. It should be remembered, for example—something Rovelli carefully avoids—that it was Albert Einstein who wrote to Roosevelt urging the United States to develop the military program for nuclear energy, fearing that Nazi Germany would get there first . That Einstein later became an unassailable icon of pacifism is another story, one that concerns the Cold War and the risk of nuclear conflict between the great powers. That Germany, now on the brink of collapse, did not develop the atomic bomb is yet another story. The Soviet Union certainly would have done so anyway, having far greater resources and a first-rate scientific apparatus.

The widespread need for the United States to acquire nuclear weapons is also demonstrated by the fact that Oppenheimer, notoriously close to the then-legal American Communist Party, was placed in charge of the Manhattan Project, both through direct sympathy and through family ties. This, as is well known, led to his long persecution during the McCarthy era. Oppenheimer, too, immediately realized the devastating scope of that weapon. After the first successful test, dubbed "Trinity," in the New Mexico desert in 1945, Oppenheimer—so passionate about ancient Indian philosophy that he studied Sanskrit to read it in the original texts—uttered a phrase attributed to the god Krishna: "Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds." And Oppenheimer, too, immediately after the war, addressed the issue of controlling nuclear weapons, the solution of which he saw in the sharing of information between states and scientific communities (which strengthened the accusation against him of sharing intelligence with the enemy). That solution, moreover, was adopted during the so-called détente and the various international protocols on nuclear arms control. Now, it's true that the phrase "time does not exist"—very New Age and pop, fun to post on Instagram, less so for explaining relativity and quantum physics—made Rovelli a literary celebrity, but that doesn't mean history, much less physics, can be approached through ideological lenses . Dramatic times, such as those in which entire populations had to choose between life and death, deserve at least a certain respect.

More on these topics:

ilmanifesto