Mallarmé in pieces

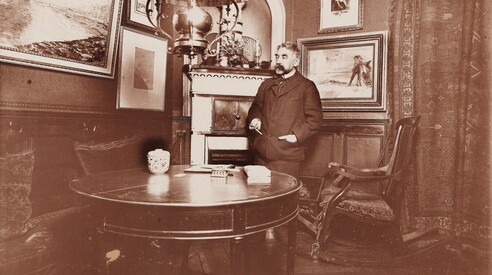

Stéphane Mallarmé with a pastel by Manet behind him between 1895 and 1896

Magazine

Books, letters, and objects at the antiques dealer Vrain. This is how we delve into the life of the professor who, in secret, changed the course of poetry.

On the same topic:

The first item on the list is also one of the most expensive. It is copy number 88 of the first edition of “Le corbeau. The Raven,” by Edgar Allan Poe, translated by Stéphane Mallarmé , “with five lithographed illustrations by Edouard Manet,” published in Paris by Richard Lesclide in 1875. On the right side, the cover bears the painter's handwritten dedication in pencil to a character familiar to visitors to the Musée d'Orsay: “À mon ami le Dr. Gachet,” meaning “le bon docteur Gachet,” from the two portraits by Vincent van Gogh, that man in the sailor jacket with a shock of Titian-blond hair sticking out from his cap, who was a psychiatrist, a great patron of “fuori salone” painters of the time like Paul Cézanne and Claude Manet, and a terrible Sunday painter. Those thirty years of French art and literature history, enclosed in thirty square centimeters of red-lettered cardboard, are priced at €120,000 and are non-negotiable. However, antiquarian publisher Jean Claude Vrain tells me that he might adjust the price of lot number 105, which has piqued my interest, due to old university backgrounds. It is a letter dated May 5, 1891 from the “father of symbolism,” the only definition known to more or less everyone of this poet who, if high school students were less stupid with their programs, could instead be proposed as the “father of rap” (try denying that the Fedez of “Inside my eyes / War of the Worlds” doesn't have some influence on “I contemplate myself and I see myself as an angel! and I die, and I'm back”) to Édouard Dujardin, author of “Les lauriers sont coupés,” in Italian “The laurels without fronds,” whom James Joyce recognized as the inventor of the interior monologue and with whom he always tried to become intimate, in vain.

The "father of symbolism", if there were fewer gnocchi with the programs in high school, could instead be proposed as the "father of rap"

“My dear friend,” Mallarmé writes to Dujardin, cleverly playing on the writer’s surname, who was then the editor of the “Revue wagnérienne” and who had entrusted him with a column, upon receiving the first copy of “Antonia, tragédie moderne,” one of the very first free verse dramas, and “La comédie des amours,” both published by Vanier: “Here you are, a primitive, a true garden (du vrai jardin), among all these flowers with uneven stems, some at foot height, in the hands of others, your verses.” They are two pages on cardboard, costing ten thousand euros; Vrain tells me it could go down to seven thousand. For now, I’m content with the catalogue, sixty euros, seen and coveted the night before, looking at it in the window, the only volume on display in six copies, while I was dropping off a friend who lives right across the street: the list of lots is printed separately for me by the assistant. Vrain didn't have a literary education, quite the opposite; at seventeen, he says, he was already a factory turner, and indeed he speaks about money with the caution and reserve of someone born into poverty. To treat money casually, looking it in the face, distancing yourself from it, you have to have always had it.

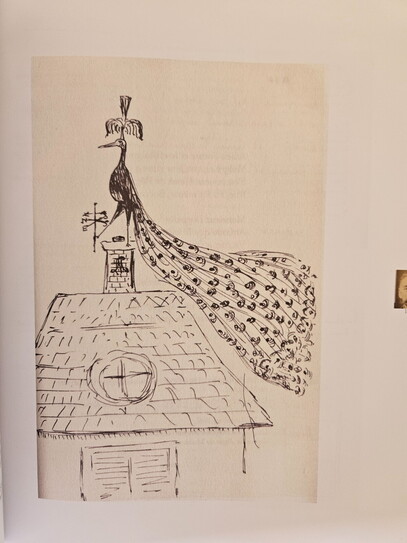

The catalog is a marvel of images and inspiration ("I called upon great scholars, you know?"): nearly four hundred pages, the fruit of countless years of research among heirs near and far ("The latest? Their surname is Paysant"), friends, correspondents, and critics. Fragments of life from an irresistible period, crucial to the construction of contemporary culture, all for sale: 322 lots—I haven't counted, but by a rough estimate—including trifles like Auguste Renoir's business card to "Madame Mallarmé with the greatest admiration" or a stunning proof etching of Mallarmé's famous portrait signed by Paul Gauguin ("à l'ami aurier, au poète"), the value of this documentary heritage is expected to exceed one million euros. One never stops leafing through and making new connections, small episodes that even a Giovanni Macchia-style study would make impossible: having all those written papers, those photos, those bibles at hand gives a sense of both vertigo and disorientation. Here is an albumen photograph of the famous "great horizontal" Méry Laurent, "garantie d'après nature"—that is, in real life—still very young, her blond hair gathered in a crown on her head, her milky breasts almost entirely exposed, a simple cross hanging from her neck with a velvet ribbon; she is the "peacock" who accompanied the poet throughout the second phase of his life, replacing his wife Marie as a confidante, who had fallen into an irreversible depression following the death of their son Anatole. And here is a rich bundle of letters from Françoise Stéphanie Mallarmé, known as Geneviève or "Vève," the owner of the famous fan that in her father's poetry blurs the boundaries between the real and the sublime. And again, a copy of Pierre Louys's "Chanson de Bilitis" materializes, that brilliant historical-poetic forgery on sapphic love that inspired Debussy, George Barbier, and even the first American lesbian association, led by the founder of the modern fantasy genre, Marion Zimmer Bradley: the copy, naturally in the first edition, from 1895, on sale for 55 thousand euros, belonged to André Gide and includes an autographed letter from Mallarmé to his friend Pierre, in which he shows that he had understood the trick, but also the many merits of that work faked as a translation from Greek. Among the treasures, Mallarmé's first letter to Robert de Montesquiou, dated November 1878, stands out. He was the model of Proust's Baron de Charlus, who at the time was twenty-four years old, pretending to be a dandy, having not yet found his poetic vein. He went looking for the translator's edition of Poe's "The Raven," published exactly three years earlier . The edition had sold so poorly that Lesclide tried to sell Mallarmé the many copies left in the warehouse, but without success due to a chronic lack of funds and also a certain bitterness over that text that no one would understand for a long time to come. Montesquiou paid ten francs for a single copy; it would be the beginning of a friendship and many evenings spent in the famous salon at 87 Rue de Rome.

Here is an albumen photo of the famous "great horizontal" Méry Laurent, the "lapwing" who accompanied the poet in the second phase of his life

Many texts have been preserved because of the lithographs and artist's proofs they contain, whether contemporary collaborations (Maurice Denis, Odilon Redon, James Whistler—it must be acknowledged that he possessed perfect avant-garde taste) or posthumous, as in the case of Matisse and Broodthaers's famous "Coup de dés." And what about the pedigree of Percy Bysshe Shelley, "printed for private distribution" in 1880, a gift from Harry Buxton Forman, bibliographer, great scholar of Keats and Shelley himself, and also a major forger of original editions, as would be discovered upon his death? Who knows what Mallarmé, the career-less English professor who struggled to arrange two refreshments for his literary Tuesdays, would have said if he had known that even the double engraved metal box in which he kept his tea, an exquisite Orientalist object, would become an object worthy of veneration, and that the collectors of his memorabilia in the 21st century would be "mostly Japanese," as Vrain says. And believe it, no one can appreciate Western hermeticism more than those who grew up on the cult of haiku, a poetic concentration of imaginative experiences and moments, but the list of enthusiasts celebrated in the introduction includes Dominique de Villepin, Paul Morel, and Pierre Bergé. His opaline glass perfume bottle costs four thousand euros (that ungrateful hyena Huysmans wrote that he was a dirty man, but it must be said that both of them were vying for Méry's favors), which is a Mallarmean object at least as much as the fan, the paper knife, the inkwell, all means of penetrating the “unknown”, portals to the third dimension, keys capable of projecting their owner into a different world.

The opaline glass perfume bottle, an object as Mallarmean as the fan and the inkwell, all means to penetrate the “unknown”

And indeed, time stands still on this morning when every reflection is suspended and everything has a price, including our hero's letter requesting editorial support from his friend, the Avignon publisher, Joseph Roumanille, for "La dernière mode. Gazette du monde et de la famille," his surreal attempt to break into style publishing with a magazine that was published for only eight issues in the autumn of 1874 and of which I am offered the cover of the zero issue (until now unpublished, like any enthusiast I own the Gallimard edition in facsimile) and the letter itself for 25 thousand euros: "Whatever you can do for your customers in favor of this publication (the only fashion magazine edited by literary men), do it, please," the poet writes to his friend, the publisher from the south, and I burst out laughing because, whether they are real, fake, presumed literary men or improvised philosophers who pile up on the stages words without meaning and clichés for the To the delight of followers and the community that should then buy belts and T-shirts, we east of the Atlantic are always at the same point with fashion: justifying its existence, trying to erase its supposed frivolity with a display, real or apparent, of culture: "I needn't tell you that its success is dear to me." Aside from the editor, Charles Wendelen, who signed the magazine with the pseudonym "Marasquin," Mallarmé was its sole editor ; he was "Marguerite de Ponti, fashion editor," he was "Ix," the society columnist, and he was "le chef de bouche Brebant," a professional chef.

Mallarmé, Vrain tells me, suddenly removing the Charles Aznavour-style cap he wears pulled low on his head, perhaps to protect his baldness from the air conditioning, arrived in 2021, after having "celebrated in my own way, with an exhibition at the Sixth Arrondissement town hall," the bicentenary of Charles Baudelaire's birth, accompanying it with a series of objects, letters, and documents from private collections (the weighty catalogue is still on sale but at half price, 30 euros). In 2022, two catalogues on Marcel Proust followed, whom Mallarmé, as a true follower of Anatole France, did not like at all (not even Gustave Flaubert, who in 1876 wrote exasperatedly to his niece that he had received "another gift from the FAVNO" (it was the "Vathek"). It would take the 20th century, psychoanalysis, for the author of the "roll of the dice that will never abolish chance" to find his critical acclaim, especially among philosophers, from Sartre to Foucault, from Kristeva to Derrida. "I approached his poetry late, I admit," says Vrain, "progressing step by step through this work that has discouraged entire generations of readers, thanks to the musicality of the verse," which is after all the only way to truly understand him, "but also by reading about him, about his character. I became fond of this professor, almost unknown to his superiors, who every Tuesday evening he transformed himself into a brilliant orator, a man of charm who sent ladies candied fruit accompanied by gallant verses and, in the secrecy of his little study, changed the course of poetry” .

A brilliant orator “every Tuesday evening,” “a charming man who sent the ladies candied fruit accompanied by gallant verses”

First a few letters, found, as always, almost by chance and out of delight, then a small obsession, developed thanks to an encounter with one of Mallarmé's last great-granddaughters, Jacqueline Paysant, co-heir to the house of Valvins, Mallarmé's summer retreat, through Geneviève's in-laws, the Bonniots. "I went to visit her several times a year in Nogent-sur-Maine. The ritual was immutable. I brought her chocolates, but more often flowers, which were immediately arranged in a vase and commented on. Then the anecdotes began, accompanied by the display of objects that had belonged to the poet." Letters, manuscripts, autographed and dedicated copies, "miscellaneous objects," and "alentours," that is, traces of Mallarmé's life in the works of his relationships: the copy of "Divagations" offered to Alfred Jarry, Méry Laurent's album amicorum containing eighty-nine autographed poems and drawings by Mallarmé—not bad at all. He missed, by his own admission, the first copy of "Coup de dés," which ended up in another collection, and Whistler's portrait of Vève, which can be admired in the Valvins museum. Currently, Vrain is working on Victor Hugo.

More on these topics:

ilmanifesto