Jane Goodall and the Library of Great Apes: Ten Essential Books About Our Closest Relatives

Jane Goodall is already wherever the great ape experts end up when they die. I imagine her in a very green and humid place in the tropical rainforest, making a place for herself next to Dian Fossey, the one who arrived first (she was murdered in 1985, as you may recall, in the Gorilla National Park in Rwanda at just 53 years old), Jordi Sabater Pi (1922-2009), who spent his life trying to distance himself from Snowflake the way Frankenstein did with his monster, or Frans de Waal, so missed for his brilliant sense of humor (who died last year at 75), who explained things about bonobos that made us blush and is one of the few people who could say they had been French kissed by a monkey.

I knew Goodall well, like Sabater Pi and de Waal, and saw her many times. Always intelligent and ironic, she could be funny or a bit rude when she thought you were wasting her time—she insisted on keeping a very tight, even crazy, schedule in her personal crusade for chimpanzees and the health of the planet —and yet she was capable of enduring with Franciscan patience what is unwritten. But how I remember her most—apart from the time we coincided in an unexpected (friendly) threesome with the actress Montse Guallar , whose brother worked with her—is when she showed enormous interest, empathy, and even passion for the hairy creatures to whom she dedicated her life ( Flo, Flint, Fifi, Goblin, Gigi, Gilka, Jomeo, Melissa ). It was an intense and profound relationship, but one in which she never allowed herself to be dragged down by anthropomorphism or sentimentality. Chimpanzees, though extraordinarily close, were chimpanzees, period. It was very clear to me that they weren't like us and never would be, that there was an impassable dividing line. And I knew that chimpanzees could be ferocious and brutal, even to the point of gang warfare, gang rape, and infanticide with cannibalism (although, I qualified, their cruelty wasn't deliberate like ours). Once, he showed me his right hand, which was missing the thumb joint that a chimpanzee had bitten off when I was trying to calm him (the poor animal was in a cage at a primate testing center). "They've dragged me, trampled me, thrown rocks that could have killed me... but they've also loved me very much," he said of chimpanzees.

Of all the things she explained to me during our time together, two things stick out in my mind: that her son Grub was kept in a cage at Gombe town center as a child to be kept out of the incoming and outgoing chimpanzees—not to be raised Tarzan-style, but to be killed and eventually eaten, as the fearsome male Frodo once did to the son of an employee (“they see human babies as the young of other species like colobuses and baboons, and therefore as potential prey”). And that chimpanzees exhibit behaviors, such as what she called “rain dances,” that suggest some kind of spirituality and even a sense of transcendence.

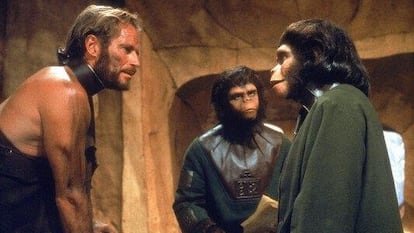

In short, Jane Goodall has left us, although her books remain, which invites us to review, along with hers, the books that would make up a library of the great apes, which we are going to inaugurate, imaginatively, in her honor. It's a library that could be in the last cabin in the Greystoke jungle or in Zira and Cornelius's laboratory in the capital of the planet of the apes (Dr. Zaius would have these books locked away). Let's select ten.

Among the titles that must be included in this library are undoubtedly those by Goodall herself. Above all, to understand her life and scientific journey, what seems to me the best of the fifteen books she wrote, some co-authored and not counting the twenty for children, is Through a Window: Thirty Years of Studying Chimpanzees (Alianza, 2024; the original edition is from 1989, this one has been revised). It is a fascinating book (I have it in an English edition that she dedicated to me with a Conradian " follow your dream " to which she added a " Good luck ") that reviews the entire experience of the primatologist during her years in Gombe Stream and captures not only a great scientific adventure but also a vital and emotional one. It collects astonishing observations and episodes, some that give you goosebumps and others that bring you to the verge of tears (like the polio epidemic). Goodall always said she was very lucky in two ways: first, being able to go to Africa to study wildlife (she said she would have studied anything, even if she'd been assigned to study dormice) and being dedicated to chimpanzees; and second, being the first person to research those apes, "because everything I saw was new and exciting."

Okay, let's add a second book by Goodall—we could add several more— 55 Years at Gombe (Confluences, 2015) , the beautiful, profusely illustrated tribute to that great adventure, with wonderful photographs. It's a very useful book for having an extensive visual reference on Goodall's life and experiences throughout her career (in fact, the book warns that some historical photos show practices that were later abandoned by the scholar and the other researchers at the center, such as touching and feeding the chimpanzees).

Another book that has to be in the selection is the memoir Gorillas in the Mist (Pepitas de calabaza, 2019), by the aforementioned Fossey, the book, originally from 1983 (many of us have it in the 1985 Salvat edition), which she wrote about her research and adventures over 13 years with mountain gorillas in Rwanda and on which the film of the same name with Sigourney Weaver was based. Fossey, whom Goodall remembered as a strange and very complicated woman with little empathy with people, was recruited as her by Louis Leakey (1903-1972), the British-Kenyan paleontologist, anthropologist and factotum who divided the study of the three great primate species between three women, Fossey, Goodall and Biruté Galdikas (the orangutans), known as the ape ladies or Leakey's angels.

From Galdikas , the only survivor of that trident of exceptional women, our library must include Reflections of Eden: My Years with the Orangutans of Borneo (Pepitas de calabaza, 2013). In it, the Canadian primatologist of Lithuanian, Estonian, and Greek descent explains her study of the great red apes in the rainforest of Borneo, specifically in Kalimatan. Galdikas has become so at one with the landscape (and the people) that she has an Indonesian passport and married a Dayak. She adores orangutans (“ gentle great ape ”) and cannot tolerate anyone speaking ill of them: she says they are the only ones in our family who haven’t abandoned paradise, but they are also losing it due to indiscriminate logging. Once I spoke with her, she told me that Fossey’s death (“Dian was very angry but also very funny”) was a blow. Then he gave me a copy of his book, the 1995 Little, Brown and Company edition, for Sabater Pi, whom I admired. I kept leaving the message from one day to the next—we're so fickle—and in the end, dear Jordi died, so I kept the book, with Biruté's heartfelt dedication: " To Prof. Sabater Pi, In admiration and respect of your inestimable contribution to science and natural history! " I have as a bookmark the letter with the photo of the orangutan from an old WWF game about endangered species.

A fifth book that I think is essential for our library is the excellent Walking with the Great Apes (Chelsea Green Publishing, 2009), a portrait of, precisely, Goodall, Fossey and Galdikas by another exceptional naturalist, Sy Montgomery , who has been described as “part Indiana Jones, part Emily Dickinson”. Montgomery, to whom we owe such formidable titles as The Charm of the Tiger (Errata Naturae, 2018) and The Soul of Octopuses (Seix Barral, 2018), met all three of them and remembered how each one tried to bring water to her mill or the coal to her sardine (monkey), assuring her that hers was the ape most similar to us: Galdikas pointed out the whites of the orangutans’ eyes, Fossey the family ties of gorillas and Goodall the 99% of genetic material they share with humans. A beautiful, illuminating book in which the author highlights how the three women became emotionally involved in their work with the monkeys.

There must be at least one book by Frans de Waal on our shelves. A good choice is his 1982 classic, Chimpanzee Politics (Alianza, 2022), his groundbreaking study of the chimpanzee colony at Arnhem Zoo (Netherlands). De Waal describes the monkeys' sophisticated strategies for seizing community power, including pacts (and their breaking).

And now, a book that Jane Goodall hated, William Boyd 's novel, Brazzaville Beach (Alfaguara, 1991). It's about a primatologist, Hope Clearwater ( Hope is the name of the stuffed chimp Goodall used), who studies chimpanzees in the wild in West Africa and who shocks (and censures) her colleagues when she discovers the sinister aspects of these animals' behavior: aggression, infanticide, pongicide, war, etc. Meanwhile, she lives a complex love affair with a mercenary aviator and recalls another one with a mathematician. The novel is beautiful, very moving, and the scientific adventures are very well described. Goodall hated it for extra-literary reasons: she claimed that Boyd had been inspired by her and had taken pieces from her books without consulting her. She also thought there was a lot of explicit sex (and Mr. Boyd, for good measure, publicity), which is disturbing when someone is inspired by you. So much sex seemed unnecessary to her, and look how she didn't mince her words when she addressed it with monkeys (and pardon the phrase).

This selection also includes another novel, Congo, by Michael Crichton (Pocket, 2003, originally published in 1980), a great adventure novel that blended classics (the search for a lost city, Zinj, in the heart of the African jungle) with scientific thriller: the expedition included a gorilla, the unforgettable Amy, who could communicate with her human caretaker using sign language and a technological interface. The knowledge about gorillas was based more on the research of George Schaller than on that of Fossey. It is one of the few novels featuring a great ape as the main character, and the only one I know of in which one parachutes.

If we're talking about quadruman novels, a must-have is, of course, Edgar Rice Burroughs' Tarzan of the Apes (edition of all his adventures by Edhasa), with a wide gallery of anthropoid characters, including the killer Kerchak , the adoptive mother Kala, Tublat, Terkoz or Bolgani . It must be remembered that Goodall - she herself acknowledged - was influenced by being called Jane. No less indispensable on the shelves of the ape library is Pierre Boulle's Planet of the Apes (B de Bolsillo, 2024), the novel that gave rise to the long film saga. Boulle's novel, whose setting was more the jungles of Indochina where he fought against the Japanese and Vichy France as a member of the Free French and the SOE than those of the apes (he would later write The Bridge on the River Kwai ), presents major differences with Charlton Heston's film. For starters, aside from the planet actually being another planet (Soror), the astronauts are French, of course. They also have a chimpanzee with them instead of actress Diane Stanley (astronaut Stewart, who unfortunately dies in the hibernation tube), which indicates poor eyesight.

There are other books (apart from the novelization of King Kong by Delos W. Lovelace , published shortly before the film's release and based on the film's script), such as Peter Hoeg's novel The Woman and the Ape (Tusquets, 1998), in which the ape Erasmus (of unspecified species), who arrives in London for an experimental laboratory, has an affair with the alcoholic wife of the scientist studying him. And there are the Mytex the Powerful comics. More ideas (and donations) are welcome for the Jane Goodall Library of Great Apes...

EL PAÍS

%3Aformat(jpg)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fbae%2Feea%2Ffde%2Fbaeeeafde1b3229287b0c008f7602058.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2F99e%2Fe92%2F595%2F99ee92595dc8484d20eaf76f014d2d21.jpg&w=1280&q=100)