In Colombia, living in poverty increases the risk of mental illness by more than 50%, research warns.

Living in poverty not only means not having enough to survive; it also means carrying an emotional and psychological burden that deteriorates mental health. This is the conclusion of a recent study led by researchers at the University of La Sabana, which warns that people living in poverty in Colombia have a greater than 50% risk of developing mental illness.

The work, titled "Poverty as a Determinant of Mental Health in Colombia: Government Policies and Perspectives," was developed by a research group at the Faculty of Medicine at the university and is one of the few national documents exploring the relationship between poverty and mental health.

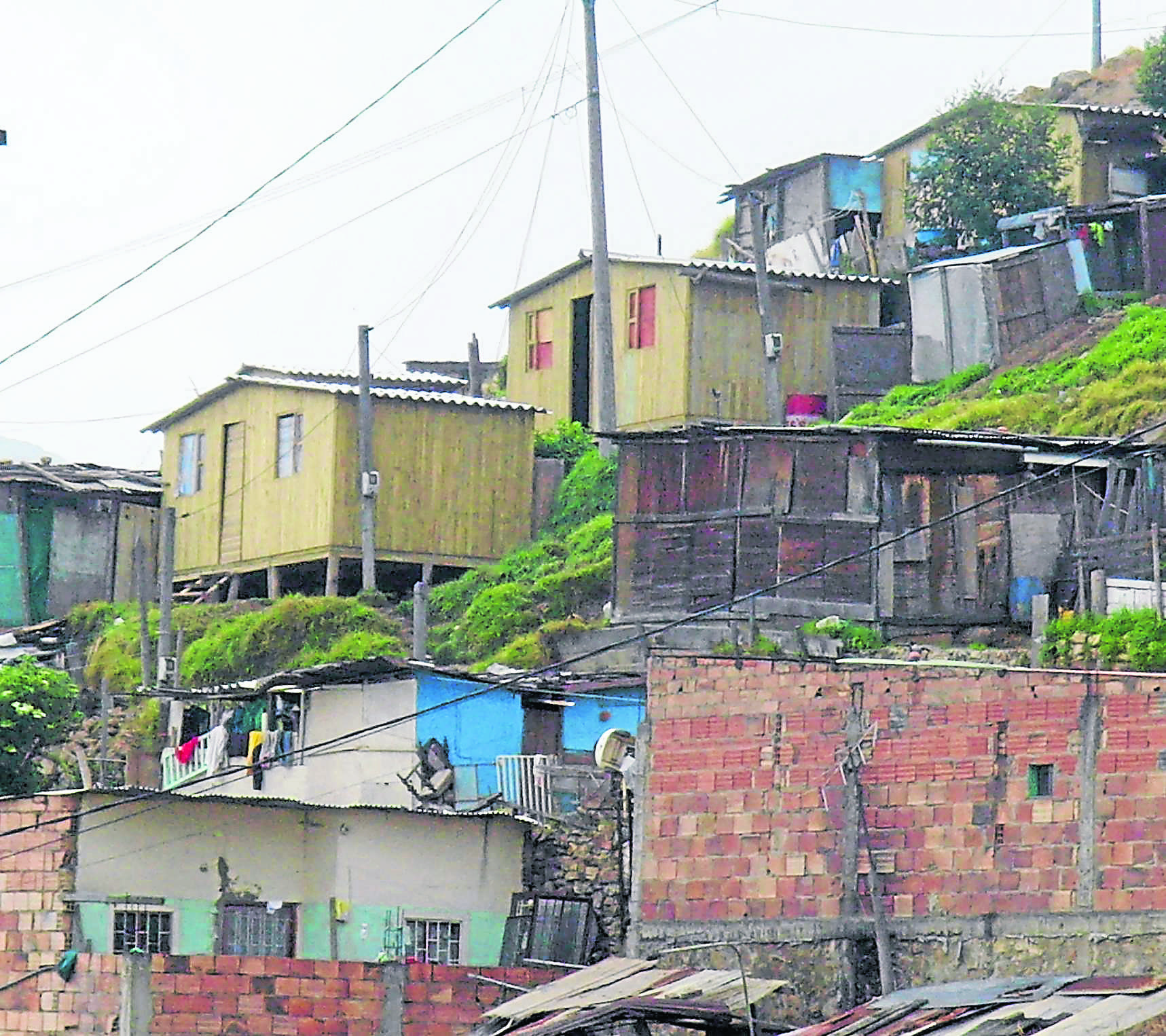

The challenge lies in implementing policies that reach the territories, experts say. Photo: Yomaira Grandett. EL TIEMPO

According to figures from the National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE), 24.4% of the population in PDET municipalities—areas prioritized by Territorial-Focused Development Programs—lived in multidimensional poverty in 2024, an increase of 0.7 percentage points compared to 2023. But beyond the statistics, researchers warn that the lack of opportunities, unemployment, insecurity, and daily precariousness translate into a public health problem that requires urgent attention.

The study was based on the concept of multidimensional poverty, understood as the simultaneous impact on two or more essential dimensions of a decent life—housing, education, employment, health, and basic services. From this foundation, the researchers applied the scoping review methodology, examining more than 345 scientific publications written between 2009 and 2024 in English and Spanish that addressed the relationship between poverty and mental health in Colombia. Finally, they selected 26 relevant studies for analysis.

The results were grouped into three broad categories: poverty and mental health, psychosocial interventions and self-regulation, and public policies. In the first, the researchers found that multidimensional poverty is a better indicator of vulnerability than monetary income.

Poverty affects almost a third of the population in Colombia. Photo: Archive

"People living in poverty have a greater than 50% risk of suffering from mental disorders," the report notes. Factors such as forced displacement, belonging to indigenous communities, chronic violence, and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic appear to be determinants that worsen anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress.

Psychiatrist Yahira Guzmán, director of research at the School of Medicine, explains that although the country faces serious problems of inequality, "Colombia does not have suicide rates as high as those in industrialized countries, which suggests that there are also cultural and community protective factors that deserve further study."

For his part, Erwin Hernández, PhD in Clinical Research, highlights the importance of structural conditions: “If you have a stable income, you feel more secure. If you have a higher level of education, you also have an advantage. Inequality is evident in the lower incomes for women and the gaps between living in Bogotá and Catatumbo, where armed violence is prevalent.”

Psychosocial interventions: rebuilding bonds and strengthening emotional control The study also explores strategies that can mitigate the effects of poverty on mental health. Psychosocial and self-regulation interventions, according to the researchers, are not limited to treating symptoms, but rather seek to emotionally empower people, strengthen their social networks, and increase the perception of control in the face of adversity.

"The important thing," Guzmán points out, "is that the intervention is aimed at finding the positive or protective factors of each population and redirecting the adversities that arise from a single determinant, such as poverty. Each community requires its own diagnosis before intervening."

Programs such as ALIVE, Semillas de Apego, and CHANCES-6, cited in the document, have proven effective in strengthening personal skills, offering financial support, and promoting emotional self-regulation. Researchers emphasize that reducing stigma, expanding support networks, and teaching coping strategies are key steps to lessening the psychological impact of poverty.

The study proposes strengthening community interventions that promote emotional self-regulation. Photo: Santiago Saldarriaga. EL TIEMPO

The analysis recognizes important regulatory advances. Since Law 1616 of 2013, which declared mental health a fundamental right, Colombia has developed a robust legal framework. This was followed by Law 2481 of 2020, which expanded psychotherapy coverage; the National Mental Health Policy of 2018, which emphasizes community action; and, most recently, Law 2460 of 2025, which guarantees psychological care without medical referral and expands training quotas for psychiatrists.

However, experts warn that the greatest challenge lies in execution. “The problem isn't in the formulation, but in the implementation,” says Hernández. “When a policy reaches the ground, resistance, lack of knowledge, and lack of financial resources arise. For mental health to become a part of everyday life for Colombians, investment and continuity are needed.”

While Colombia is making progress on mental health laws, it continues to fail in their implementation. Photo: AFP

The research concludes that poverty acts as a structural and cross-cutting determinant of mental health in Colombia. The most affected populations are those experiencing violence, social exclusion, and displacement. Although the country has an advanced legal framework, the study underscores the need to strengthen public investment, adapt policies to local realities, and foster community participation.

In the words of its authors, mental health cannot be addressed solely in clinics: it must also be addressed in schools, homes, and public spaces, where the possibility of emotional and social well-being is built day by day.

Environment and Health Journalist

eltiempo