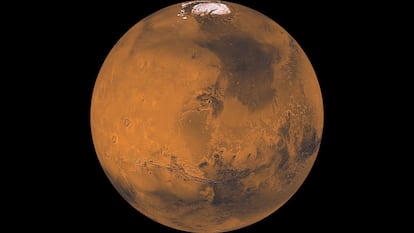

An experiment deciphers the real reason why Mars is red

Madrid - CET

A study of Martian dust , combining data from space missions and laboratory replicas of samples, suggests that it was oxidized when liquid water was widespread. “Mars is still the Red Planet. It’s just that our understanding of why Mars is red has changed,” explains Adomas Valantinas, lead author of a study published Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications and led by researchers from Brown University in the United States and the University of Bern (Switzerland).

“We were trying to create a replica of Martian dust in the lab using different types of iron oxide. We found that ferrihydrite mixed with basalt, a volcanic rock, best matches the minerals observed by spacecraft on Mars,” Valantinas, a postdoc at Brown University, said in a statement.

Ferrihydrite is an iron oxide mineral that forms in water-rich environments. On Earth, it is often associated with processes such as the weathering of volcanic rocks and ash. Although scientists had suspected that ferrihydrite was the reason for Mars' red color, the theory had been unsuccessful until now, when researchers have been able to manufacture Martian dust in the lab by mimicking observational data from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter , along with ground-based measurements from the Curiosity , Pathfinder , and Opportunity rovers.

More habitable than previously thoughtThanks to the fleet of spacecraft that have studied the planet over the past few decades, it is known that Mars’ red color is due to oxidized iron minerals in the dust. That is, the iron bound to rocks has at some point reacted with liquid water, or water and oxygen in the air, similar to how rust forms on Earth. Over billions of years, this oxidized material (iron oxide) has been broken down into dust and spread across the planet by winds, a process that continues today. But the exact chemistry of Martian rust has been intensely debated because its formation is a window into the planet’s environmental conditions at the time. And closely tied to that is the question of whether Mars was ever habitable.

The discovery would indicate that Mars was once wetter and potentially more habitable than previously thought, since unlike hematite, which typically forms in warmer, drier conditions, ferrihydrite forms in the presence of cold water. Researchers believe that Mars may have had an environment capable of supporting liquid water — an essential ingredient for life — and then transitioned from a wet environment to a dry one billion years ago.

The scientists created the replica Martian dust using an advanced grinding machine to achieve the realistic dust grain size equivalent to 1/100th of a human hair. They then analysed their samples using the same techniques as orbiting spacecraft to make a direct comparison, ultimately identifying ferrihydrite as the best match. “This study is the result of complementary data sets from the fleet of international missions exploring Mars from orbit and at ground level,” says Colin Wilson, ESA’s TGO and Mars Express project scientist.

Other studies have also suggested that ferrihydrite could be present in Martian dust, but Valantinas and the rest of the team have provided the first comprehensive proof by combining data from space missions and new laboratory experiments.

Do you want to add another user to your subscription?

If you continue reading on this device, it will not be possible to read on the other device.

ArrowIf you want to share your account, upgrade to Premium mode, so you can add another user. Each user will access with their own email account, which will allow you to personalize your experience at EL PAÍS.

Do you have a business subscription? Click here to purchase more accounts.

If you don't know who is using your account, we recommend changing your password here.

If you choose to continue sharing your account, this message will be displayed on your device and the device of the other person using your account indefinitely, affecting your reading experience. You can check the terms and conditions of the digital subscription here.

EL PAÍS