Photojournalism through the lens of Liliana Toro

The history of photojournalism in Colombia, as with many crafts and arts, has traditionally been told through the male lens. The list of great photographers who captured defining events in Colombian society through snapshots, such as the Bogotazo or the great cycling events of the 1960s, includes names like Sady González, Manuel H., and Carlos Caicedo, to name a few of the most renowned; the list goes on.

What history has forgotten is that there are several women who, for decades, have also captured with their cameras events that have shaped the country. They have done so shoulder to shoulder with those figures highlighted in books, retrospectives, and exhibitions. Although new female names appear every day on the map of news coverage, the percentage of women cannot match that of their male counterparts.

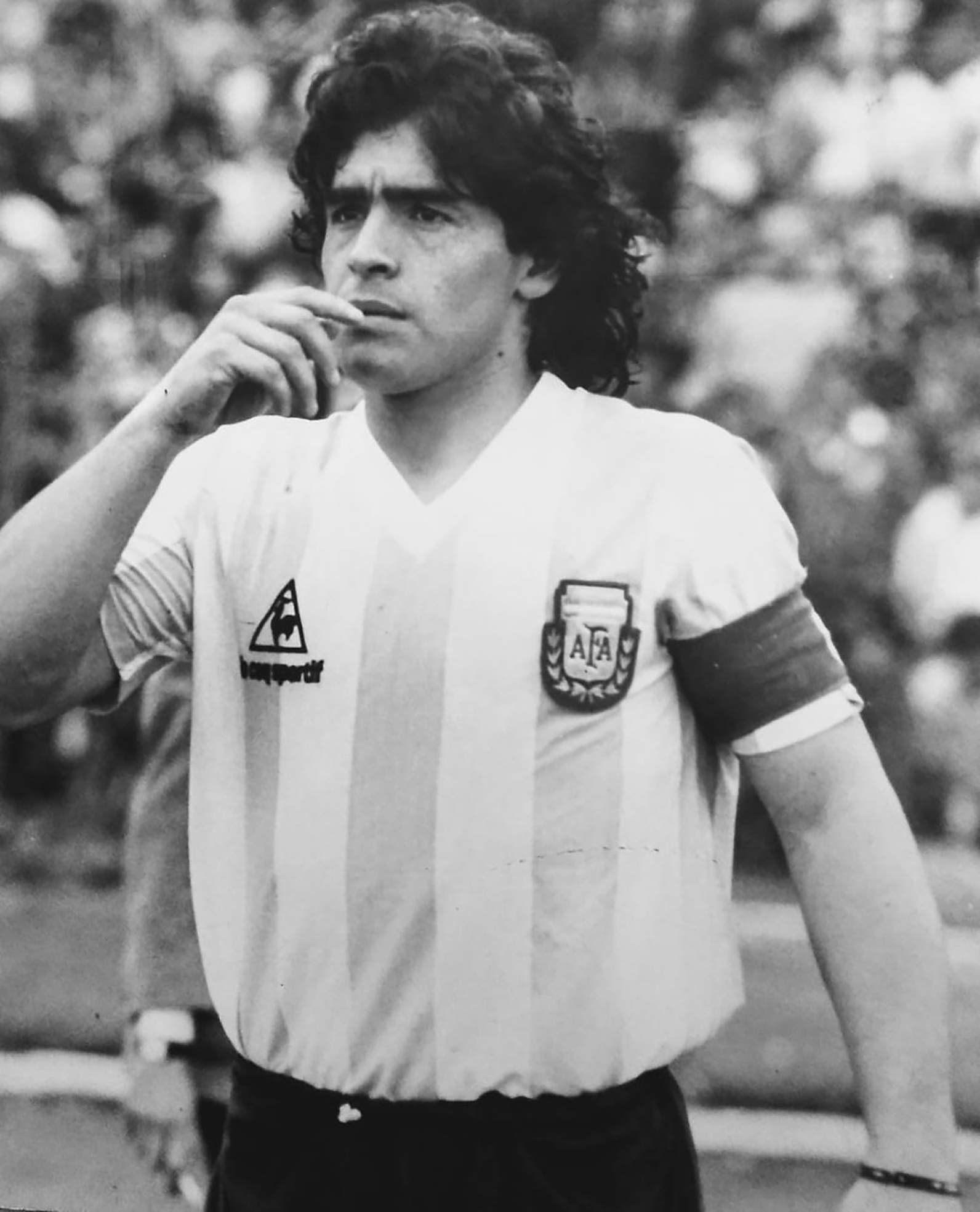

Among those women is Liliana Toro Adelsohn (64), who since 1982 has worked for various media outlets such as EL TIEMPO, El Gráfico, El Espectador, and Revista Cromos. Her first assignment as a photojournalist for a media outlet was a night soccer game. She didn't know her colleagues, all of whom were men, and even less knew the technique of sports photography. "When I entered the stadium, about 15 photojournalists approached me and asked me who I was. Very scared, I told them: 'My name is Liliana Toro and I work for El Pueblo de Cali,' and I turned away and left them talking alone because I was shaking all over. I was the only woman there, and for 20 years I felt alone."

Photographer Liliana Toro exhibits her photographic work spanning over 40 years. Photo: Liliana Toro

In her more than 40 years as a photojournalist, unlike many of her colleagues, Liliana never exhibited her work. Until she yielded to the proposal of her colleague Freddy Beltrán, who insisted on holding the exhibition for nearly three years and is also the curator of the exhibition "Under My Lens," at the Alliance Française in Bucaramanga, which will run until October 4.

When did the idea of doing this exhibition arise? I've always kept a very low profile. I don't like awards, and exhibitions even less. Fredy suggested I do this exhibition, saying he thought I deserved it, but we never got around to it, until this year he said, 'Well, Mona, I've already secured the exhibition space.' He gave me a hard time, but I accepted. I already had everything selected because I'd been doing that work, box by box, with my analog work, which is the majority. The digital part is another stage of my life.

What period of your production does the exhibition cover and what are the main themes of the photographic exhibition? It's my analog work. It runs from 1982 to 2000. I have sections on politics, culture, public order, daily life, and personalities. At the end of the black and white section are my macro photos of flowers. It's a project I began five years ago, during which I have dedicated myself, disciplinedly, to taking one photo a day after leaving reporting. The result is a selection of 124 beautiful flower photos. It's my signature work at this point in my life.

Photographer Liliana Toro exhibits her photographic work spanning over 40 years at the Alliance Française. Photo: Liliana Toro

It was very complicated because we did everything through video calls, where they showed me how one wall was looking and another with the photos I liked the most. I sent 150 negatives by courier, trusting that everything would turn out well because they're unique. Sometimes, photojournalists don't have a large archive because we work with media outlets that kept them. In my case, I have some negatives, but I had to rescue others from the prints.

What is the oldest photo in the exhibition? It's an article by Héctor Lavoe that was published in 1981 in El Espectador's Sunday Magazine. I wasn't working for them at the time. But I went to the concert and took some photos because I adored Héctor and was a salsa fan. A friend told me those photos had to be published, and they did. From then on, being a salsa lover, I went to all the concerts and interviews. I have an impressive salsa archive with photos of Celia Cruz, Tito Puente, and Alfredo de la Fe. Later, I was hired by El Pueblo de Cali to be a photojournalist in Bogotá.

At what point in your career did you start seeing women accompanying you on your coverage? Pancha, Esperanza Beltrán, my colleague at El País de Cali, was the first I remember. She didn't go to the stadium because she only covered politics. I taught her how to cover soccer, and she taught me what she knew about Congress, which wasn't so easy. Then, in the 1990s, I started seeing more women covering the news. I remember Eliana Aponte and Gladys Barajas. But the coverage was always very masculine, and it still is. Exaggerating, you'll find a maximum of three women, compared to a large number of men.

Photographer Liliana Toro is exhibiting her photographic work spanning over 40 years at the Alliance Française. Photo: Liliana Toro

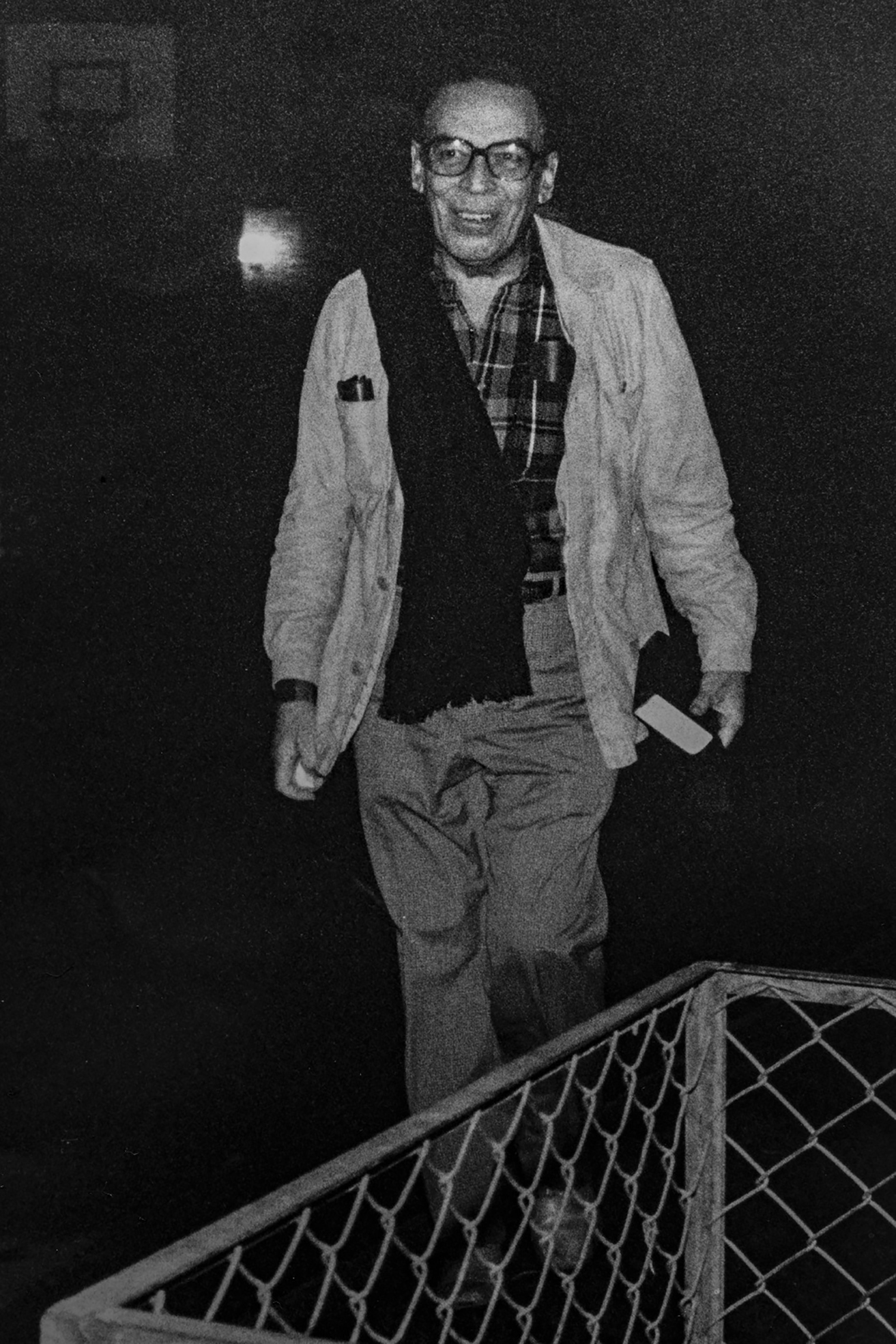

I had to make my own way and have a lot of character. In 1988, I was called to work at EL TIEMPO. That year, Álvaro Gómez Hurtado was kidnapped, and one night they sent me to stand guard because they said they were going to release him, but he never showed up. The driver, the journalist, and I were on probation. The next night they sent me back. I was very nervous with my cameras and kept recharging my flash to make sure it was working. While we were waiting, the journalists and photographers went to get something to take, and I didn't go. Then I saw Dr. Gómez walking with a scarf and a Bible in his hand. I turned on the flash and took the first photo. When he entered his building, I took the second photo. Then the whole press came, and I climbed into the patrol car in front of his building, which faced a wall, and that's how I was able to jump in. There I took the third photo. Everyone stayed outside. I arrived at the newspaper, and everyone was waiting for me, including the Santos family. That's how I got into EL TIEMPO, which was one of my dreams. Álvaro Gómez's photo is the one that opens the exhibition and the one that convinced me to continue working.

When looking at your photographic work, it's impossible not to come across the famous photo of 'Tino' Asprilla, in which his private parts are visible during a 1993 match. What does that photo represent in your career? Tino's photo will be in the exhibition in its smallest size and with a magnifying glass so people can take it and look at it. I don't want to give that photo any importance because it just happened; it's not a photo I composed or have ever seen. That day I went to the stadium on assignment from the newspaper El Gráfico for the Colombia vs. Chile game and had to dedicate myself exclusively to taking photos of Tino. In one go, I took three photos and felt they turned out well. The journalist, while looking at the developed negative, noticed something in the photo and started shouting, but I didn't know I had taken it.

eltiempo