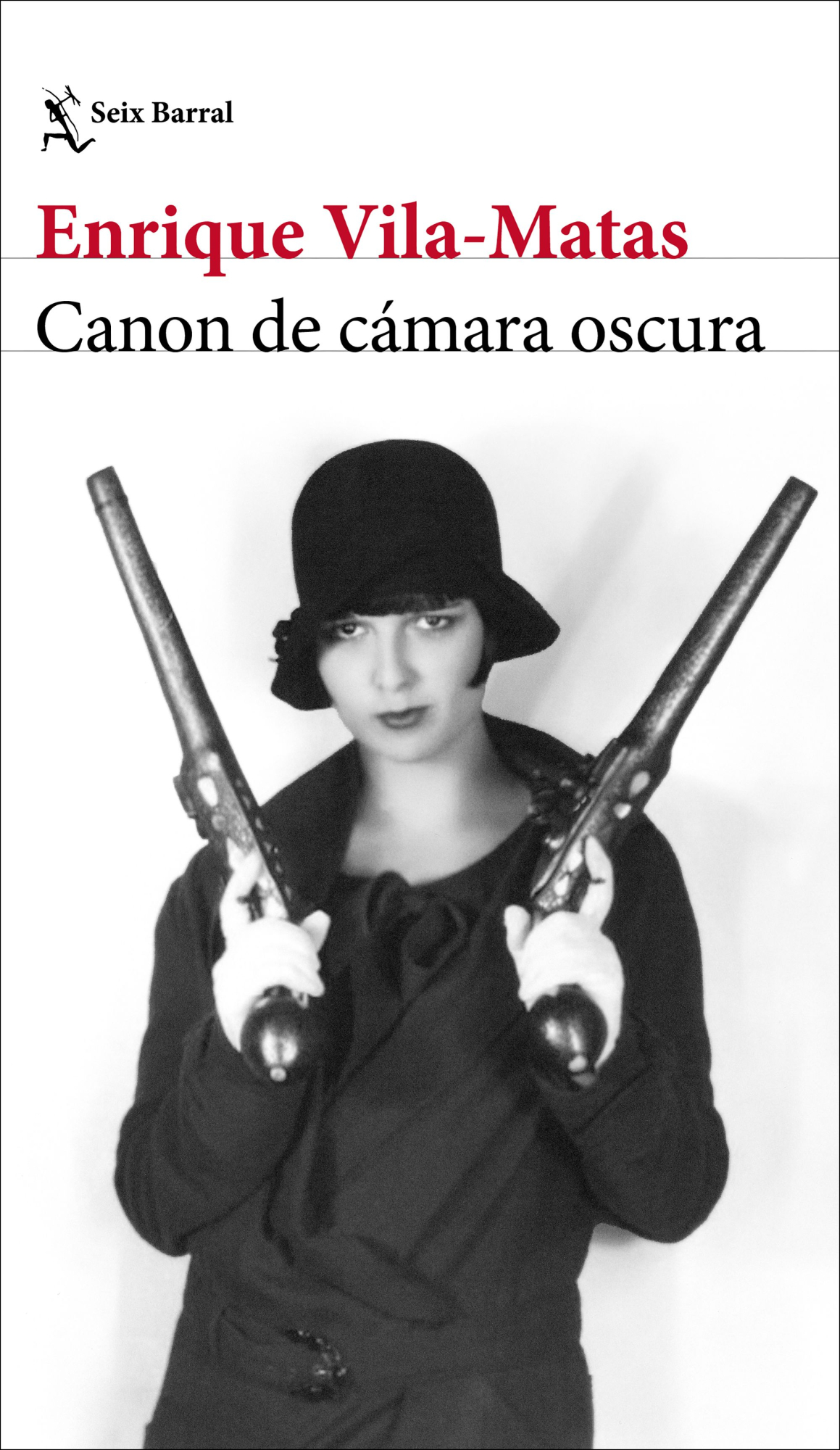

Enrique Vila-Matas returns with "Darkroom Canon" and an android in love with world literature. Interview

The Spanish writer returns with a science fiction novel in which androids are the least important element. This is his Camera Obscura Canon.

Do androids dream of literature? Enrique Vila-Matas seems to answer this question—paraphrasing Philip K. Dick and the story on which Blade Runner was based—in Canon de Cámara oscura, his new novel, where the boundary between the human and the artificial blurs in the ever-shifting territory of literary creation. If in Historia abreviada de la literatura portátil (Abridged History of Portable Literature), Vila-Matas reinvented the canon through irony and erudition, and in Bartleby and Company he explored the fascination with silence and the refusal to write, in this work he goes a step further: now it is an android, Vidal Escabia, who takes on the task of narrating and selecting the essential books of his own canon, following the "Great Blackout" that has left Barcelona plunged into darkness and given life to a legion of androids that are becoming increasingly human.

Spielberg reinvented the Pinocchio myth in Artificial Intelligence. Photo: Warner Bros.

And yet, Camera Obscura Canon is not a science fiction book, or so Vila-Matas himself assures: “It was a claim to draw attention to the book, but with a warning that it wasn't about science fiction. Rodrigo Fresán, an Argentine friend who lives in Barcelona, said it was a science fiction book, that it made science fiction. A new genre. I think I agree with that.” Because, beyond the androids who become more human as we read, this new novel-essay is, in the best Vila-Matas style, a text that discusses the worlds offered by reading, the worlds proposed by the art of reading.

Sentient and literate replicants were born in Blade Runner. Photo: Warner Bros.

Far from being a simple collection of titles, Canon de Cámara Obscura is a literary artifact that engages with tradition and contemporaneity, challenging the obsession with lists and hierarchies. Vila-Matas's great success is that, through humor and playfulness, he manages to give the reader a master class in literature. And to achieve this, he turns his android narrator into a mirror that reflects both the literary heritage—Kafka, Borges, Beckett, Marsé, Luiselli—and the uncertainty of a present dominated by algorithms, fragments, and the temptation to forget. Canon de Cámara Obscura is a return to the most literary, most fragmentary, most delirious, and most bookishly passionate Vila-Matas. Talking to Vila-Matas (and especially reading him) is like encountering an intelligent, erudite, loving, and entertaining voice about books: "I've defined myself as a reader of phrases, of books. At first, it made me angry, but now I think it's wonderful, because there were readers who told me they had to thank me for books they didn't know and that they had read thanks to me. Of course, I would prefer them to tell me they thanked me for the book I had written, but then I started to think it's great, because it's a project I do with other people. A collaborative project, with other readers, with other writers." And now he's risking creating his own untimely literary canon.

In the world of literature, the idea of the canon is an obsession. From time to time, the media publishes lists of the best books: academia produces more canons than graduates. Why do you think this obsession exists?

The first question they asked me when the book came out was if I was very interested in canons, and I said, "No, not at all. I'm not interested in canons." I said it in the same way Juan Marsé responded when he was asked in our Sunday social gathering if he agreed with the way politics was handled in the city. He took the floor to say, "Here, in this social gathering, we're against everything." It seemed like an ideal response to me because you shouldn't separate one thing from another. "Everything," and that was the end of it. I thought that in what I'd done, I'd always opted for something more marginal. Something far from the famous canon of the American Harold Bloom, which for me was a kind of grotesque and boring nonsense, where he separated Shakespeare from the others and ignored great writers, anyway... I thought the book was in favor of what wasn't canons. It was a coherent part of the world I've tried to establish in my books.

This 71-book diary follows neither chronology nor hierarchy: how did you balance the tension between chance and necessity in the selection and order of the texts? What role does disorder play in this book?

An important word for me was chance. I selected, or said there were, 71 books in the canon's darkroom. But I discovered the titles of the books as I wrote, and some were surprising. I also didn't feel obligated to include the books I liked, because I'm always riddled with doubts. I know which books interest me more than others, but I didn't feel it was a declaration of principles of mine, so I included books in the canon that I really liked and that were part of what I took seriously, but without the need to include some whose absence would hurt me greatly. In the end, there are only 30 or 35 books up for grabs, because if I had made the complete canon, the book would have become long, and everything in it is very concentrated, very brief, very intense. The problem was that it could become endless.

Canon camera obscura Photo: Private archive

An infinite canon would almost be the annihilation of the canon, wouldn't it?

The problem with lists. That's why I limited the story to two days where I summarize the previous 35 books. I find the list mania amusing. Actually, there's a list at Christmas, in Colombia there's a list of the best books of the year, in Spain too. The lists are always incredibly unfair. They're made by people who haven't read anything, not even 1% of the year's books. This used to be a problem only at the end of the year; now there's the summer list, the last summer's list, the list from the first of this month. Here in Spain, this list thing is very justifiable. I see it as justified because behind it lies the publishing phenomenon of continually publishing books. So when the lists come out one month and the next, you shouldn't give them the slightest credit, whether my book appears on it or not. That way, I'd de-dramatize this whole congestion of lists that Georges Perec would love, but he'd certainly laugh at them.

The book defends the fragment. You call it a crack in the totalizing edifice of language. What is the power of the fragment in literature?

I think it's incredibly important; it's the vindication of the book. The fragment is what makes it possible to continue talking about what happens within a world so complex, so fickle, and so elusive. I think the failure of Robert Musil, who wrote his great book, The Man Without Qualities, day after day, lies in the fact that the book becomes increasingly complex, and he must stop writing it when it has too many pages. This failure foreshadows what is to come, which is the absolute confusion of the century we find ourselves in. It's abundantly clear that current reality, what is happening, can only be accessed through the fragment. The other thing is trying to tell a story that addresses everything in its entirety, and I really don't understand that. In this respect, all best-selling books that tell a story are similar, as in the 19th or 18th centuries, where, with great artistry, they sometimes tried to cover the entire world in a single book. That seems absolutely idiotic today.

And in your writing, what does the fragment represent?

It's very clear that the fragment has a lot of power in what I write. A personal fact is that I really enjoy a book like this—with 21 fragments—because of the freedom that comes with starting each fragment, where I can say whatever I want in the first sentence. Literature is also a struggle to be able to say what you want to say, even if you'll never say it.

At one point, the android narrator says that his teacher, who was his former owner, is “one of the few brave narrators Barcelona has ever had.” What does a brave narrator mean to you?

This stems, in part, from what I had read about how a writer has to risk his life like a bullfighter before a bull. That is, truly risk his life in what he wrote. This was Michel Leiris's thesis, which I've been considering for years. And this idea of bravery also came from the abundance with which this adjective, in the early years of the century, was applied to our friend Roberto Bolaño. I asked myself: "Brave, but in what way brave?" I was aware of his bravery personally, but not so much in terms of the text. And well, I also related that bravery to him, to those phrases of Bolaño's that have become so famous...

It's like the writer is a gladiator who jumps into the arena knowing he'll lose, but jumps into the arena anyway. I love and still love that phrase. I would also quote some verses by Bolaño himself, in which he talks about the disaster of his life in Blanes and the rejections of all his books by publishers. He says: "Here writing poetry in the land of imbeciles, rejections from all the publishers, but with Lautaro, my son, sitting on my knees, doing nothing, but writing. All very bad, but writing. Writing would be, then, the last chance of heroic survival on earth." And yes, it's true. I've always thought about writing a text titled 'But Writing.' We all already know everything that came before, but still writing.

In that "but writing," the image or figure of the failure appears, a recurring theme in your books. What attracts you to failure in literature?

Because it's inherent to the passion for literature and the attempt to transform the literature of our time, which is practically beyond the reach of almost anyone. Failure accompanies the practice of writing. It's a bit funny because the first time I thought about all this was when a friend, Professor Ivette Sánchez, Venezuelan of German origin, invited me to a conference on failure at her university in Switzerland. Well, I was thoughtful there; it seemed like she was giving me up as a failure so soon, right? But for a very serious reason, in which I had to go to another European city for a prize, in which money was awarded, I put this before failure. She was very upset that I wasn't going, but the biggest difficulty was finding one of my friends who wanted to go to this conference; everyone felt involved.

Have you ever felt like a “failure”?

I hadn't heard the word "failure" until reading Julio Ramón Ribeyro. His diaries, which are marvelous, revolve around failure. Then I also realized that the word "failure" is often used by sports journalists: "Do you think your team will fail on Sunday?" And more things like that. It doesn't upset me or worry me. I understand that whatever I tried, I would fail, even if I tried something minimal. Therefore, I have the feeling that if I started out wanting to transform, through what I was writing, the literature of my time, well, now I have to admit that I have to calm down because I see that I won't achieve it. And if I did achieve it, it would create a huge problem for me. So everything's left up in the air.

"You seem very dominated by literature," they tell the narrator, as if carrying too many books were a form of submission. Do you feel there's a loss of freedom—or perhaps its exact opposite—in that life 'possessed' by reading?

Yes, you hear people say that: "You only think about literature." Well, no, not at all. When I think about literature, I live elsewhere. There are clichés, attacking people, that say: "You're too literary and not very human." I play with irony because my narrator, if he becomes more human, they'll kill him. He would like to become more human, but he can't because he'd be captured, shot down like a terrorist. And these are ways I invent to address the possible accusations that arise in real life, like: "You're not very human, you're always reading," as if one could separate one thing from the other.

In fact, Camera Obscura Canon is a book about androids, even though it's not entirely about androids. What was it like to write in the shoes of a robot?

What I have highlighted most when attacking this point of the book is that I had the sensation, being an android narrator with a double mind, of experiencing a sensation I had not experienced until then: that I could actually say whatever I wanted and think whatever I wanted.

But hasn't he always been free as a narrator?

Yes, but in this case, having affirmed my freedom allowed me a personal experience: that of unleashing the possibilities of the android's original mind, which had been manufactured in the United States. Having two minds, I thought I could arrive at something within a personal investigation into the origin of android language. For example, the phrases that didn't seem entirely mine, that perhaps meant something else, that came from somewhere else, allowed me to discover what language the android that arrived on Earth and began to humanize after the general android blackout in the city of Barcelona came from.

The narrator says he lives in "an illegible world." Do you think the purpose of this scattered canon is to recover some legibility, or rather to point out that reading today means accepting chaos and fragments?

He speaks of the illegible and, above all, of the unspeakable. The unspeakable is a term coined by Marguerite Duras, which meant that in a moment of total chaos, everything serves as unspeakable, and everything is. And it points to the general confusion. The unspeakable is always in writing. It's in what we've talked about: failure. It's easy to realize that, if you think about it minimally, you see that we never manage to say anything we want to say. And that's why I think it's very good that the author of the book himself previously wrote an essay titled The Unspeakable. It's one of the problems that literature has always had: that no one will say what they should say.

Another recurring theme in this book is the relationship between writers and their desks. To the point that the narrator wonders if he's becoming a desk that tells stories.

I found the ideal quote on this subject in John Banville. He said that on weekends he was terribly bored because he had to pass for a human being and preferred to stay at his desk, where he had everything, including his mind and his creativity. I loved this quote because it was exactly what I thought. It's funny because Banville is so bored on weekends, but I think he's married to two women at the same time; but, well, I don't know, he must have a lot to do on the weekends. In any case, I agree with what he said about how if you take him out of there, he has less fun, since the possibilities he has to write a book with the imagination and intelligence available to him are immense. I wouldn't know how to be without imagining, thinking, creating, inventing. It's the center of my fun. In fact, when I'm not writing and, let's say, I'm on a bus or something, I try to be really mean to someone I really disliked, if possible a writer, so I can speak badly of them. And I'm surprised that, with all the thinking, imagining, and inventing I do every day, I have so few books. Anyway, mentally, and even more so over time, I find writing much more fun than watching a movie.

What was the funniest moment while writing Canon of the Camera Obscura?

What I enjoyed most, because I was moved, was when I found some verses by Lope de Vega. I was amazed because they described my way of structuring the book or my books. But above all, when I read a fragment from Dante's Divine Comedy, which seems like science fiction when Beatrice and Dante's gaze lock, and they travel beyond space and time. It's told in a way that strikes me as high poetry, but it also seems like science fiction. Besides, it was where I wanted to talk about the exact center of the book, which would be eternal love, the love that lasts a lifetime; you can feel that in the book.

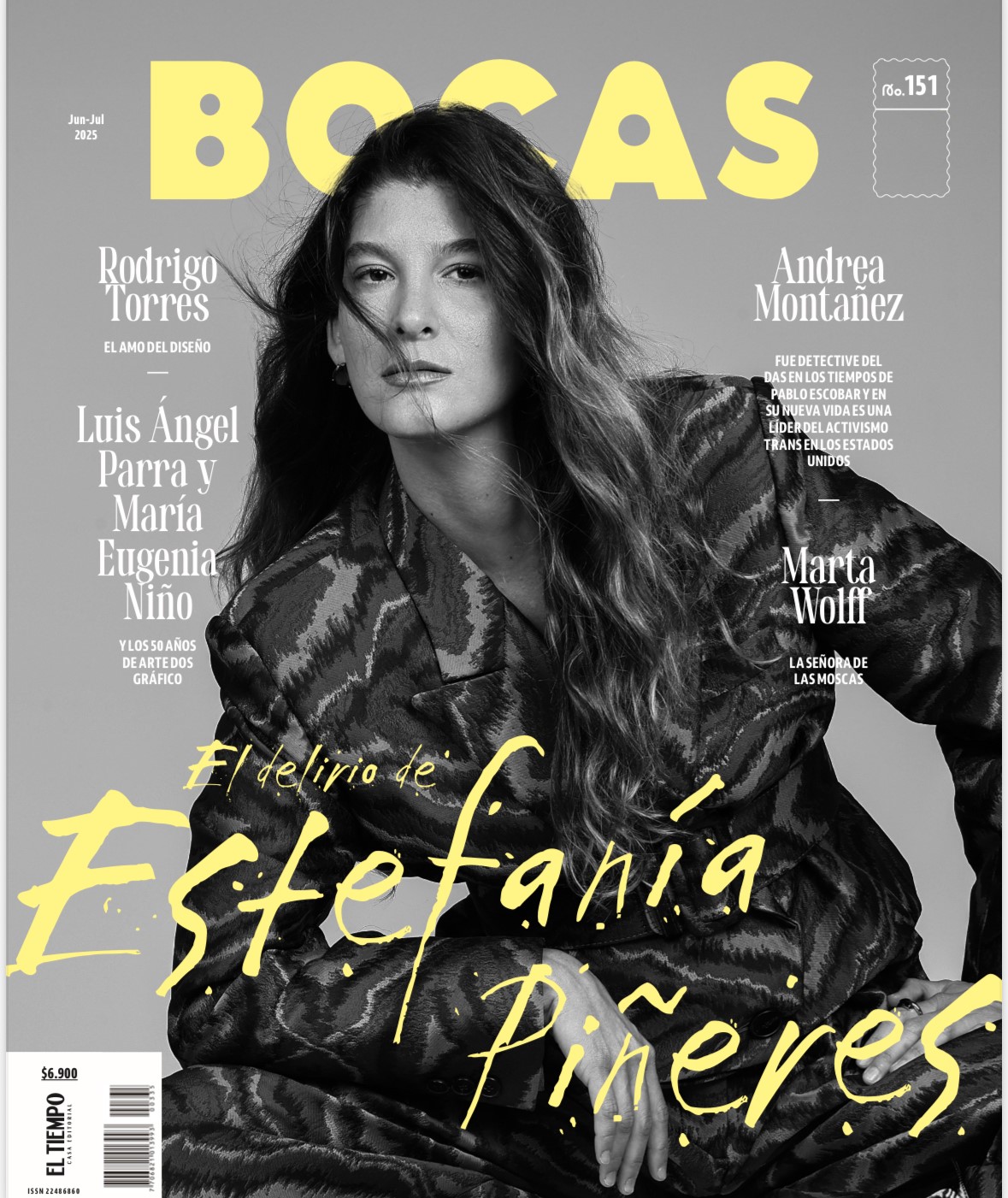

Recommended: Estefanía Piñeres and Delirio

Cover of Bocas magazine featuring Estefanía Piñeres. Photo: Hernán Puentes / Bocas Magazine

eltiempo