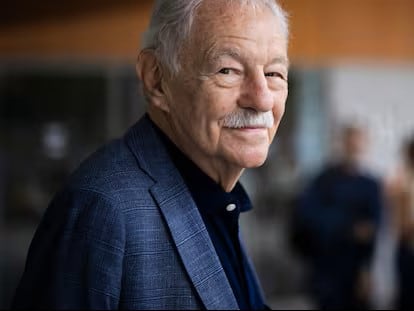

Eduardo Mendoza: surprising the world and drowning at home

A type of opinion piece that describes, praises, or criticizes, in whole or in part, a cultural or entertainment work. It should always be written by an expert in the field.

The urban setting of perhaps the most outstanding novel by the recent Princess of Asturias Award winner , The City of Marvels , explains the transformation of a provincial town into a cosmopolitan metropolis. It also explores the misgivings between Madrid and Barcelona and the origins of the contempt, even hatred, toward the Bourbons held by a large portion of Barcelona's citizens. A city park can tell all this.

“On the eve of the opening of the Universal Exposition , the authorities had pledged to rid Barcelona of undesirables.” That same phrase, which Mendoza dates back to 1888, shortly before the opening of the first Universal Exposition held in his city—and in Spain—was heard again several times in Barcelona. Not coincidentally, it happened during the preparations for another major event that was to transform the metropolis: the 1992 Olympics . On that occasion, the transvestites we mingled with at night on the Rambla de Catalunya and the prostitutes, of lower standing and lower budget than those in Pedralbes, who worked at the end of the Ramblas, were evicted.

We've known that it takes years to pay for the Olympics. Especially when one of the national sports consists of going all out to display power. In preparation for the second Universal Exposition, which was held in Barcelona again in 1929, Mendoza recounts that "every two hours, as much water was required as the entire city consumed in Barcelona in an entire day." For this second Universal Exposition in Barcelona —the second in Spain and in the same city—the city had a Greek theater (El Grec), a Spanish village (with traditional buildings from various Spanish provinces), and... one of the most modern buildings in the world: the German Pavilion, now reconstructed and known by the name of its designer, Mies van der Rohe. "All at once," he writes.

But, for Mendoza, perhaps the most striking feature of that Universal Exposition was the luminous fountain, “the fountain on a slope of Montjuich mountain , a pool 50 meters in diameter and 3,200 cubic meters in capacity surrounded by fountains that moved 3,000 liters of water powered by five 1,175-horsepower pumps and lit by 1,300 kilowatts of electricity. It changed shape and color. Everyone could see it. It surprised the world and drowned people at home.”

Barcelona was suffocating in the 19th century. The main problem was... housing. Housing prices were sky-high because the city was imprisoned by the ancient Roman walls . While Paris had 7,802 hectares and London 31,685, Barcelona residents lived on 427. Mendoza recounts that while Paris's density was 291 inhabitants per km2 and London's 128, Barcelona had 700 people living in that space "because the government wouldn't give permission to demolish the walls and, with unsustainable strategic pretexts, prevented Barcelona from growing in size and power," he writes. Where did this suspicion, which seems so current, come from? Mendoza embodies it in his prodigious novel.

“In 1701, Catalonia, jealous of its liberties, which it saw as threatened, embraced the cause of the Archduke of Austria in the War of the Spanish Succession . Once that faction was defeated, and the House of Bourbon enthroned in Spain, Catalonia was punished.” The Bourbon armies plundered Catalonia. “It was with the connivance of local leaders,” explains the Cervantes Prize winner. What did the plunder consist of?

There were hundreds of executions "as a mockery and lesson, their heads were impaled on pikes and displayed in the most crowded areas of the Principality. Many cultivated fields were razed and sown with salt to render the land barren; fruit trees were uprooted." Attempts were made to exterminate livestock, especially the Pyrenean cow. Some fled to the mountains. Castles were demolished and their ashlars used to enclose the walls of some towns. Monuments in squares and avenues were crushed, reduced to dust. The University of Barcelona was closed. The port was stocked with sharks brought from the Antilles. "Perhaps this lesson will not be enough for the Catalans," said Philip V. That enlightened monarch, Duke of Anjou, had a gigantic fortification built in Barcelona. An occupying army lived in the Citadel , ready to suppress any uprising. There, sedition suspects were hanged and left to feed on vultures. But... "Inactive soldiers are always a danger: they get bored, don't get promoted, and last too long." Paradoxes of life: prisoners of duty and hatred, the soldiers lived imprisoned in their Citadel.

In 1848, there was a popular uprising. Espartero considered it more expedient to bombard Barcelona from Montjuïc Hill, and the city recovered the grounds of the Citadel. The City of Marvels narrates how, to house the 1888 Exposition, a public park was created there. Today, the Catalan Parliament meets there. The park is a symbol. Also an emblem. It represents a historical erasure and also a rectification. Likewise, the writer—not sparing any criticism—speaks of the "rickets of conception that often characterizes our local administration." There are no forests or large groves there. There is a past, history, explanations. And, paradoxically, remains of the first Spanish Universal Exposition that transformed Barcelona into The City of Marvels .

EL PAÍS

%3Aformat(jpg)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fbae%2Feea%2Ffde%2Fbaeeeafde1b3229287b0c008f7602058.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2Fbd2%2Fe90%2F7a5%2Fbd2e907a569ebeebd9fc42bee4511ddc.jpg&w=1280&q=100)